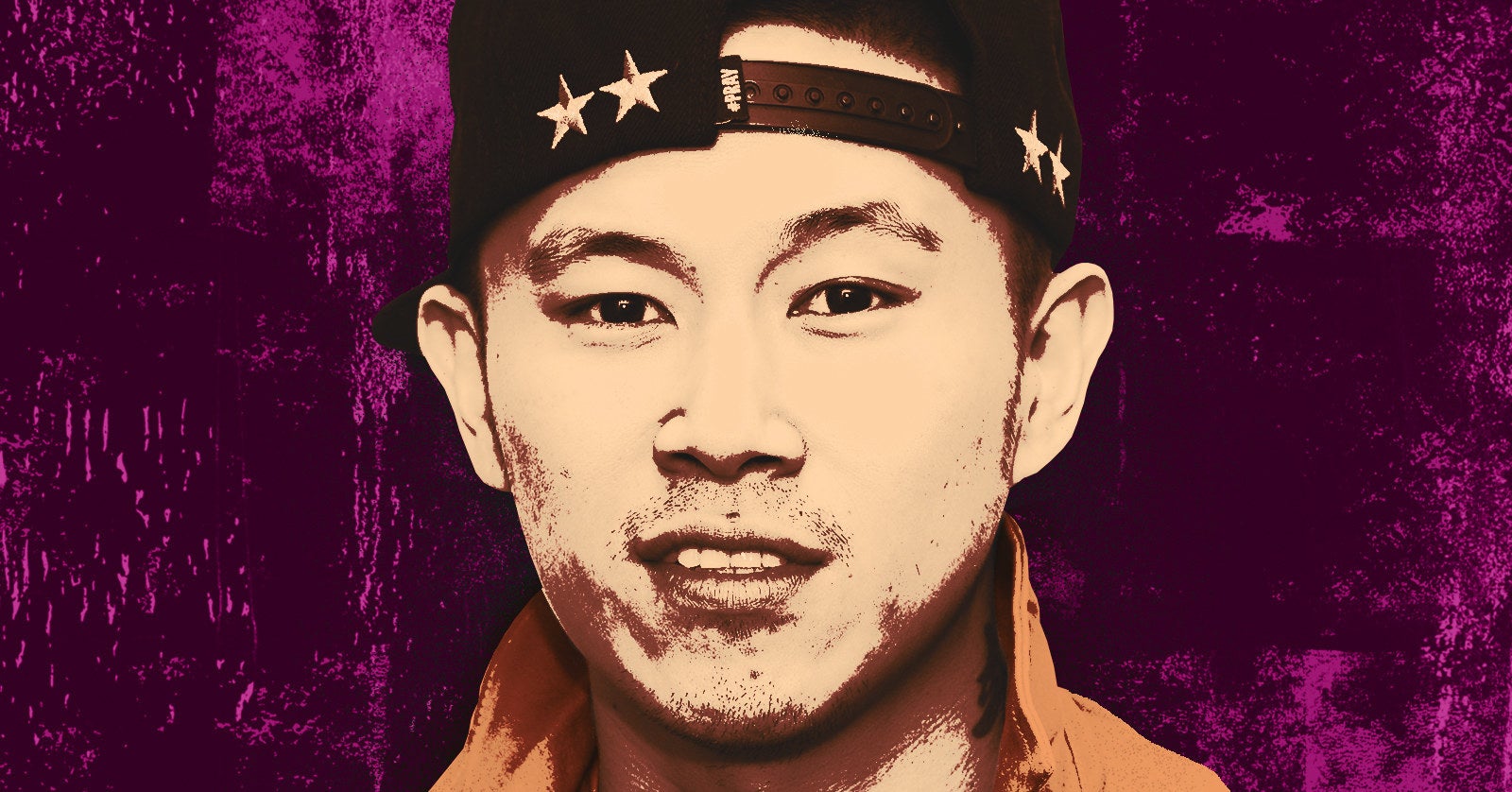

MC Jin — real name Jin Au-Yeung — grew up in his parents’ restaurants. When he wasn’t at home or school, he was at one of the three Miami-area locations that his parents ran over the course of his childhood. Like many kids who became part of the Chinese restaurant dynasty by default, he took orders, did his homework, bused tables, and watched TV during slow hours. He hated it. But when he got his driver’s license as a teenager, tasked with delivering orders for his parents, things changed.

Jin’s first priority upon hopping into his Honda Civic wasn’t the food; it was rummaging through his CD stacks to find the perfect album to listen to as he drove around. Maybe he’d put on Puff Daddy’s ’97 album, No Way Out, or DMX’s debut, It’s Dark and Hell Is Hot. Helping out with the family business was his responsibility, a nonnegotiable nod to the filial piety expected in Chinese culture. But it was also his own time, a chance to feed his obsession with hip-hop, “a crucial component during those days,” Jin told BuzzFeed News in late April.

“As a first-grader, my world was divided between school and the restaurant. And then we’d go home to sleep. My whole universe was the takeout restaurant,” he said. In every clichéd and sincere way, music was his escape.

Jin didn’t just listen to hip-hop; he studied it and wrote rhymes. He cyphered at school and eventually made his own music. He would become the first Asian American rapper to sign with a major record label — no less than Ruff Ryders Entertainment, which fostered DMX and Eve. He became a legend on 106 & Park’s “Freestyle Friday” battles. His 2003 single “Learn Chinese,” an unapologetic demand that people adjust to his culture, became a viral hit. He became an unofficial figurehead for the AZN Pride movement, an expression of Asian American solidarity in the early aughts.

MC Jin is not a household name to most Americans — but to Very Online Asians of that era, like myself, he was the face of growing up Asian in the US. He wasn’t Black, but his identity was naturally shaped by his proximity to Blackness. He wasn’t white, and he was reminded constantly that he would never be able to access the same kind of power as that community. He was Chinese, in the US, and proud. But he was always moving through other people’s spaces.

In 2021, Asian Americans are fighting for awareness and against anti-Asian racism, spurred by recent hate crimes. I wanted to talk to Jin at this pivotal point and ask him how he’s grappling with a movement that is stronger than ever. Once a figure who helped put Chinese American creatives on the map, Jin is now, like so many of us, continuing to cultivate his own space in the US. Today, he’s almost 40 and married with two young children (one of whom is “so cognizant” of racial issues right now, he said, “especially with the Stop Asian Hate movement”). While the AZN Pride movement sought to highlight various elements of Asian identities, we’re now embarking on a more grounded and enriched exploration of our diaspora. And MC Jin’s life and career are emblematic of our evolution.

MC Jin and Wyclef Jean onstage at SXSW in 2015

Jin was born in 1982 in North Miami Beach. He and his sister were first-generation Americans; at home, his parents prepared Chinese food, played Cantopop, spoke Cantonese, and encouraged the children to also speak it at home. Some of his earliest family memories involved the four of them watching Hong Kong action films together. In fact, looking back, he said, some of his most successful tactics during rap battles came from kung fu movies. His favorite actor was Shaolin Soccer lead Stephen Chow, who has appeared in some of the highest-grossing Cantonese films ever made. It was the way he physically jostled his opponents or playfully baited them that Jin would later infuse into his bars.

“There was a certain brand of humor that his movies always carried,” he said. Jin noticed a similarity between kung fu and rap — both mandate that you counter what your opponent has thrown at you. In the heat of a battle, he would often think, OK, how do I take that and flip it back? Writing rhymes, he would remember Chow’s style and ask himself, How do you inject that wittiness? How do you deflect? How do you self-deprecate in a balanced way?

He said he had a fairly “run-of-the-mill” childhood. When he wasn’t at home or at the restaurant, Jin hung out with a close circle of friends he’d known since he was 6 or 7. They were a diverse crew — “one Haitian dude, one Jamaican dude, and a Chinese kid” — and they would get into “mad adventures” around the Miami area. “We all kind of shared the same passions, but hip-hop definitely was at the center of it,” he said. “Out of the different genres, the one that just yanked me by the neck and said ‘you’re mine’ was definitely hip-hop.” As a young teenager, he watched, closely studied, and eventually emulated rappers like LL Cool J and Kris Kross. “At that time, I was a sponge,” he said.

MC Jin’s life and career are emblematic of our evolution.

Hip-hop also helped him unwind from long days at the restaurant. As a kid, he would loaf around until his parents closed the restaurant at 10 p.m., although they rarely left on time. “When I was younger,” Jin said, “there was this notion of ‘When school’s over, you’re coming to the restaurant because we’re not going to hire a babysitter.’” Every day after elementary school, he walked 15 minutes to the restaurant. He’d sit at the one designated table unoccupied by patrons and do his schoolwork or entertain himself until his parents closed shop.

As a teenager, he was the guy answering the phone for pickup orders. He was the guy taking in-house orders and also the guy his dad would send to the supermarket if they were short on ingredients. He sometimes also helped deep-fry egg rolls and chicken wings in the back. Jin looks back on those days with some gratitude — “I was lucky that I had that restaurant to be in and run around and eat all the chicken wings that I wanted,” he quipped — but as a teenager he felt resigned and at times “miserable.”

Jin was physically working, but mentally he was elsewhere — daydreaming about being so good at rapping that he’d be famous. He’d gained some notoriety already at his high school; he and his friends would start cyphers in the cafeteria, where he’d practice the rhymes he wrote at home and at the restaurant.

His grand plan to become MC Jin the rapper — he often referred to himself using his third-person moniker — was both escapist and accessible. “We had a little TV in the restaurant,” he said. It was the late ’90s, and the Notorious B.I.G.’s “Mo Money Mo Problems” was everywhere. “I’m like, that’s it. You know? More money, more problems. I want more problems. I don’t have enough problems,” he joked.

Sometimes he’d say to himself, “Yo, I’m gonna be a rap star.”

“It’s a little more superficial and a little more naive, right?” Jin said. “[I] was just like, ‘Yo, I’m gonna get a deal.’”

His parents were generally supportive — or perhaps he was so “hell-bent” on the rap thing that they chose to nurture it rather than fight it. Jin said his parents knew early on he was not going to become “the scholar of the household” or focus on academia. His mom “came around quicker” to his music pursuits and helped fund a recording session for his first single when he was in high school. For a while, his dad was stuck on the stigma of hip-hop culture; the music was portrayed as dangerous in mainstream media, negatively associated with violence and drugs. Jin wanting in on the culture both confronted his dad’s prejudices and helped him expand his tolerance for it — a difficult and familiar dynamic typical of tensions between Black and Asian communities. “I’m 15, coming home, telling my dad, ‘Yo, this is what I love.’ He only sees that side of it,” Jin said. “Now he’s more open-minded than I probably am in terms of receiving and appreciating cultures, particularly hip-hop.”

MC Jin in Times Square in 2003

After his family closed their last restaurant, they moved to New York City. He was 19, a self-described “nomad with a bookbag.” He carried around a boombox he’d saved up for and played beats around the city. Wandering around Manhattan and Queens, where his family had settled, he met other rappers to freestyle with on-site, and performed at open mic nights. Occasionally he’d stop in Manhattan’s Chinatown to visit his grandmother, who’d cook him a meal.

Jin’s capital-B Big Break came in 2002, when he appeared on the “Freestyle Friday” segments on 106 & Park, a show where local amateur rappers were invited to battle in front of a panel of celebrity judges and a studio audience. Jin won seven battle weeks in a row, a huge feat in and of itself, but he also encountered racism, which was striking, yet somewhat normalized in the ring. For seven weeks, he was jabbed front, right, and center with Asian jokes and slurs. (“Why you got me battling Bruce Lee’s son? / Leave rap alone and keep making fortune cookies,” one of his opponents rapped.)

Jin’s combat skills were carefully crafted; he’d been training to counteract racist quips with something more clever. “You want to say I’m Chinese? / Here’s a reminder / Check your Timbs / They probably say ‘made in China,’” he spat back in one battle.

At the time, he wasn’t “thinking about these racial dynamics” critically. He had blinders on for becoming famous. Jin was signed almost immediately following his “Freestyle Friday” streak, but the high would be constantly interrupted by the sobering reality of being the first and most visible Asian American rapper in the industry.

Being Asian in a predominantly Black genre, within a predominantly white music industry, Jin ended up leaning on his identity while also questioning how much of his success was due to being the token Asian. Would he be denied a chance at success because he’s Chinese, or would he only get that chance because he’s Chinese? Would anyone take him as he was? He’d think to himself, The most important thing is I’m here, you know? I got skills.

Would he be denied a chance at success because he’s Chinese, or would he only get that chance because he’s Chinese?

His first brush with fame made him hyperaware of how he was presenting himself. Jin had adopted fashion and speaking cues from hip-hop culture. He had to do a kind of “balancing act”; he was heavily influenced by a culture he deeply admired, but he was not trying to present himself as Black. Constantly reminding people he was Chinese in his music was one way he centered his racial identity. Profiling Jin for the New York Times in 2004, Ta-Nehisi Coates noted that his strategy of playing on “Asian-American stereotypes while trying to rebut them” put him in an unenviable position. “In emphasizing his ethnicity so blatantly, Jin risked turning himself into a oddity,” Coates wrote.

“If I don’t acknowledge I’m Asian or Chinese in some fashion, then it becomes, Look at this dude; he thinks he’s Black for real,” Jin said. “I don’t think I’ve ever wanted to be Black. Do I admire Black culture and Black people? Absolutely. But I’ve only wanted to be Chinese. … I’m still navigating this.”

Phil Yu, the Korean American writer behind the popular Angry Asian Man blog, was captivated by Jin’s talent and meteoric rise when he started his site in the early 2000s. His forthcoming book about Asian American pop culture icons, Rise, features a whole section dedicated to the rapper. Jin’s confidence and braggadocio onstage was “so empowering to see as an Asian American man,” Yu told BuzzFeed News. “Asian men in our society were not allowed to do that; we were not allowed to be loud or confrontational.”

Still, while Jin’s race made him stand out onstage, it also overshadowed his talent. “I still think people didn’t give him the respect he deserved as an artist, because he was Asian,” Yu said. “A lot of people saw him as a gimmick, despite him being such a skilled and accomplished battle rapper. It was a hard hill to overcome. When he put out his first record, it had to lean heavy on his Asianness and make it his thing, [but] I don’t blame him for that. What else is he going to do?”

His breakout single, “Learn Chinese,” exemplifies that focus on his racial identity. The song was self-parodying, with a catchy hook (“Y’all gon’ learn Chinese”), throat-punching lyrics (“We should ride the trains for free / We built the railroads”), cliché “oriental”-style string arrangements, and a few lines in Cantonese, all over a classic ’90s hip-hop beat. It was his first single after being signed, and it was produced and co-written by Wyclef Jean.

According to Jin, Jean was the “brainchild” behind “Learn Chinese.” The Fugees rapper advised him to play up the persona that helped him win “Freestyle Friday” battles — the one that’s aggressively, self-referentially Chinese.

“He was like, ‘We saw what you did on ‘Freestyle Friday.’ Clearly, the fact that you’re Asian and you’re Chinese and your ethnicity is something that they’re going to continue coming at you with, the way they came at you during the battles,’” Jin recalled Jean telling him. Jin’s debut album, The Rest Is History, contained references to “the Great Wall” and Yao Ming, as well as some wordplay about his race.

But being the first Asian American rapper backed by a major label came with high expectations. “Learn Chinese” got radio play and peaked at No. 74 on the Billboard R&B and hip-hop singles chart; he still remembers the euphoria of hearing his song on the radio station Hot 97 for the first time. But it did not sell many records.

Jin in the video for “Learn Chinese”

Music executives and media personalities hyped him up in interviews, playing into a nescient logic that if he simply appealed to the world’s Westernized Asian population, he’d sell billions of records. “People were saying to me, ‘There are billions of Asian people. … If 1 out of 4 buy your album, you’re going to be huge. And 20-year-old me was like, ‘You’re right, I’m about to kill it,’” he said. “Lo and behold, my album drops, and it hits nowhere near what the general projection was. There is this sense of, Oh, guess he’s not the one.”

Despite being a mainstream flop, “Learn Chinese” was a fringe internet sensation. Its release coincided with the AZN Pride movement of the late ’90s and early 2000s, a fun but haphazardly organized online celebration of being Asian American across early social media sites like Xanga, Myspace, and AsianAve. Defining that era requires confronting its cringey elements: embracing Asian stereotypes and punchlines, Blingee doll GIFs, AIM screen names like xX_AzN_BaBy_Angel_Xx, and import car shows.

Phil Yu also struggled to define AZN Pride as a cohesive moment, which was perhaps both its point and its problem. “What is it really? Is it an aesthetic? Is it people being really proud of being Asian?” he said. “I always found it kind of weird that it wasn’t enough to call ourselves ‘Asian’ — we had to call it ‘AZN.’ Is that acknowledging that saying ‘Asian’ wasn’t cool enough, that we had to call it ‘AZN’?”

Jin reminisced about that time like many of us still do. He ran through a checklist of the movement’s iconography, which felt like a starter pack meme for being cartoonishly Asian. “A lot of spiky hair, although I never had the spiky hair,” he said. “A lot of emphasis on car culture. … People calling [the cars] ‘rice rockets,’ which is semi-cringe. But, yeah, we were about our [Toyota] Supras and Honda Civics.” Through a now-defunct forum site called AZNRaps.com, Jin said, he was able to connect to fellow Asian hip-hop heads in a way he wasn’t able to before.

MC Jin in Hong Kong in 2008

It did foster community, he said, but it was also a “shallow” effort that was mostly about aesthetics.

“AZN Pride reflected something we’re still embattled with, but I feel like we’re making headway,” Jin said. “The impact of it was definitely more online. It was great that internally it created a certain energy that was healthy in terms of embracing your culture. But do I feel like it created a shift on the bigger stage? Probably not.”

AZN Pride was a sometimes flimsy and two-dimensional way to corral cultural unity, but it was a new frontier for first- and second-generation Asian Americans. Like it did for many other communities at the time, the internet introduced a lot of young Asian people who might not have grown up around many other Asian people. The movement had a message that hadn’t been proclaimed before: “We are Asian and we are proud.”

With “Learn Chinese,” MC Jin was brazen and defiant about being East Asian in a Black and white America, and he was ambiguously elected the mayor of the movement. He didn’t realize what kind of impact the song had on the Asian American community until Asian club promoters began booking him to tour and make appearances in San Francisco and Vancouver venues before he’d even announced an album.

The content might have been frivolous, but the intent was there: In 2003, we were looking to define ourselves by the clothes we wore and the cars we drove. In 2021, we’re looking deeper. It’s no different for Jin. “What we’re dealing with right now, with the Stop Asian Hate movement … unfortunately, it’s in the midst of death and tragedy and mayhem,” he said, citing the rise of reported crimes against Asian Americans over the last year. “But I do think there is a shift occurring right now, where more of our stories are being shared, and maybe because there is a sense of urgency.”

He’s a father now, to two young boys. Jin now tries to process his experiences and traumas about race through their lens. “I’m not necessarily trying to mold [my eldest son] into an activist, but I want him to carry that pride with him,” he said.

After the spa shooting in the Atlanta area in March, Jin and his wife took their children to a Stop Asian Hate rally in New York. “I don’t know how much impact it will have on him, but I would like to think that 20 years from now he’ll remember,” he said.

“I would be heartbroken if I ever heard him say, ‘Yo, daddy, why do I have to be Asian?’ He hasn’t said that yet, but I have heard him say, ‘Why are Asians getting attacked like this?’”

MC Jin speaks and performs at the Rally Against Hate in Chinatown in New York City on March 21.

Jin said the current movement is forcing him to reflect more “in depth” about how he’ll talk about his Asian identity in public, in future music projects, or with his eldest son, who is 9. “What do I want him to know about me?” he now asks himself.

“Hip-hop has given me so much; it’s given me everything,” Jin said. “But I’m very aware that this culture is not birthed from my own racial and cultural heritage. Does that mean I can’t have a valid or authentic experience in it?”

Today, he feels he has more room to make music in Cantonese and for a Chinese audience. Some of his more recent projects were released exclusively in Hong Kong. In 2011, he collaborated with fellow Asian rappers Dumbfoundead and Traphik on a joke song called “Charlie Sheen” that also played well online. And while his first US-backed album flopped, a Cantopop album called ABC (an abbreviated slang for “American-born Chinese”) he released overseas years later under Universal Music Hong Kong sold well and propelled him to fame there. Jin wasn’t wholly defined by being an Asian American artist in Hong Kong; he was, more simply, an artist whose music broke through.

“I’m very aware that this culture is not birthed from my own racial and cultural heritage.”

In 2014, he released a song called “Chinese New Year.” It did not make much of an impact commercially, but it was extremely personal. He said it was a “deeper” proclamation of his heritage than “Learn Chinese.” If his first commercial single demanded that people accept his Chinese background, “Chinese New Year” is a soliloquy about self-acceptance and the challenges of being a pioneer. “For your safety / I went through the crash test,” he raps. “Life is a road trip / Can’t rely on MapQuest.”

Music is not the escapist dream career Jin had imagined. He joked with me that as work and travel opportunities evaporated over the past year, he thought he might have to “go down to Home Depot and see if they’re hiring.” His imprint on Asian American culture has scored him several speaking gigs at college campuses over the last decade. Nowadays, he’s campaigning hard as part of Andrew Yang’s bid to become mayor of New York. One thing about Jin’s music hasn’t changed; in a music video he put out last month for the Yang campaign, he can’t help but make a few quips about his racial identity: “I’m back for the ride / And I’m still rockin’ my ‘math’ hat to the side.” But he’s quick to remind us that he’s not backing Yang purely because of his race. “An Asian candidate that’s dope,” he raps. “As far as my support, though, that ain’t even why / The War on Normal People opened up my eyes.”

This month, he released a new song, “Stop the Hatred,” another collaboration with Wyclef Jean. “After witnessing the uptick of heinous hate crimes against the AAPI community in the recent year, I wanted to use my artistry to express some of my own sentiments as well as raise awareness on these issues,” he posted on Instagram. “The song title was inspired by my 8 year old son, Chance, who boldly shouted ‘Stop the hatred’ into a crowd of thousands at a #StopAsianHate rally in New York City.”

I asked Jin how he’d feel if one of his sons pursued hip-hop. Jin chuckled, then paused to think it over. “I would tell him, don’t worry too much about how people see you. I guess that’s very generic, [but] I’ve had to navigate that over the years,” he said. “With my rhyming, that intensity, I was seeking some kind of validation, as an Asian man or not. It was a paradox. That probably was what drove me so hard. On one end, I don’t really care how you see me, but it was also, I care so much how people see me.

“If I could say something to Chance,” Jin said, “I’d say, ‘Focus more on how you see yourself.’” ●