For his debut solo exhibition in Los Angeles, London-based artist Alvaro Barrington hosted an all-day barbecue in the Blum & Poe gallery parking lot and invited Ghostface Killah to perform. From the pop-up stage, the Wu-Tang Clan scion looked out on the crowd and bashfully called it “mixed”; there were adult Ghostface fans as well their children, plus moneyed art collectors who had come to buy new, very in-demand work. What ensued was, in modern parlance, iconic – a half-hour singalong of Wu-Tang hits, with bonus tracks commemorating the late Biz Markie and Marvin Gaye. There were even product samples of Killah Bee, Ghostface Killah’s gold-speckled, cannabis-infused brownies. The opening was uplifting, in every sense of the word.

“The show wouldn’t have been complete without Ghost,” Barrington said. His exhibition, 91–98 jfk–lax border, on view at Blum & Poe through 30 April, is an acutely personal look back at the 90s through hip-hop, an unvarnished record of an era ripe for closer examination.

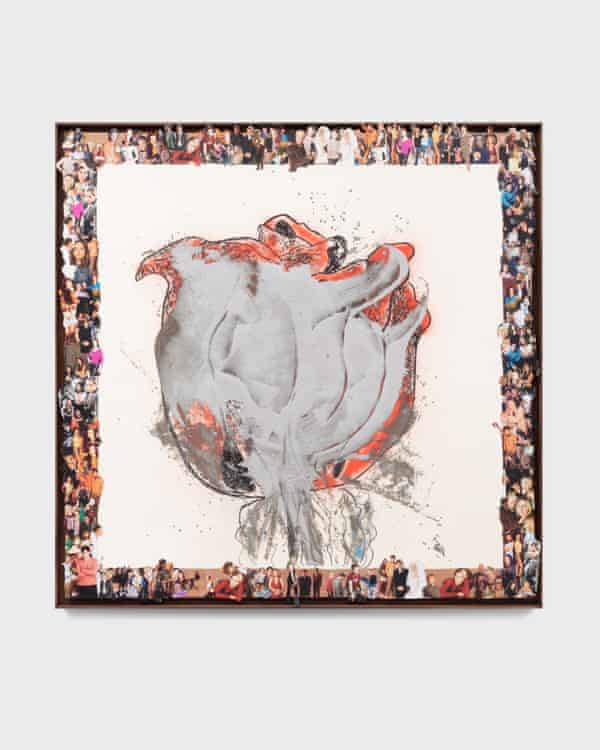

In 1990, when Barrington was eight years old, he left his home in tropical Grenada. He and his mother moved to Flatbush, Brooklyn, the West Indian enclave of a much larger, concrete island. With the same approach as recording an album, he organized his show to include features – that is, guest appearances – by other artists who resonate with elements of the community: Teresa Farrell, Aya Brown, Paul Anthony Smith, Jasmine Thomas-Girvan, and his teenage cousin, Ariel Cumberbatch. The wall-mounted sculpture by Thomas-Girvan bears “a kind of magic realism that is so deeply Caribbean”, Barrington says, in its sinuous assemblage of wood, costume feathers, and strands of brass curled to resemble plumes of smoke. He compares her work to a trumpet solo that Olu Dara, Nas’s father, played on a track of the Illmatic album: “It’s reaching down to the roots, but it’s also reaching to the heavens. It gets you to this place of serenity.”

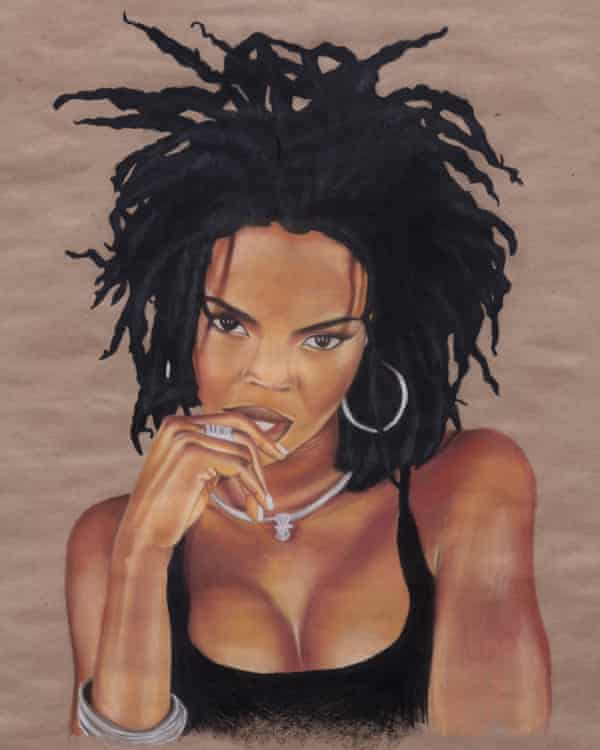

Brown’s portraits of Missy Elliott, Lauryn Hill, and Li’l Kim, rendered in soft pastel on brown kraft paper, had reminded him both of a specifically New York style of drawing, and the way punk rock had influenced the work of Elizabeth Peyton.

“In music, you understand the role of a feature; it’s kind of the antithesis of painting, where we think of the painter as an individual genius,” Barrington says. “But Aya looks at these women in a way that I can’t represent myself. The lesson I learned from hip-hop is that it makes more sense for her to speak in her own voice.”

In his own works, Barrington chose materials that would evoke the textures of his childhood, assembling basketballs and milk crates, rebar and cement, into homages of two of the greats, 2Pac and DMX. “I see Pac and X as a continuation of each other; they both tell the story of the war on drugs as a war against working-class black communities,” the artist says. “When politicians were calling young Black men newly released from prison super-predators, X was talking about what being locked in a hole would mean for a 14-year-old’s mental health.”

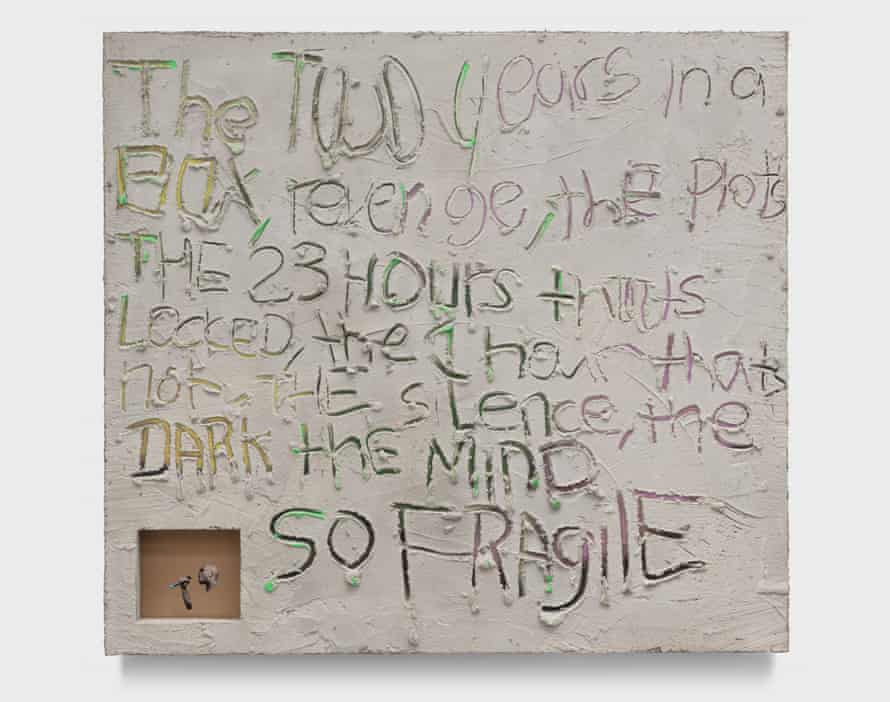

Homages to DMX bookend the exhibition, beginning with two floating monuments mounted to the gallery walls. Cut-out images of the rapper, microphone in hand, are encased in cement boxes that Barrington inscribed with lyrics while the cement was still wet:

The two years in a box, revenge, the plots/ The 23 hours that’s locked, the 1 hour that’s not/ The silence, the dark…

Those 23 hours reverberate into a separate gallery space, where, in contrast to the colors and textures of the show as a whole, a row of cold steel frames line the perimeter of completely white walls. Within each frame, a cardboard panel cut with the digits of a quartz alarm clock bears a time, from 00 to 23h00. They amount to a day in solitary confinement the way that DMX had described – a prolonged, silent procession of hours.

In both nostalgic and mournful turns, this is a show about history, both public and private, and who counts as a reliable narrator. Looking back at the 90s, Barrington describes the decade as a “fundamental shift in the American imagination”, where neoliberalism’s veneer of prosperity glossed over increasingly punitive measures against communities of color. He recalls Bill Clinton charming Black audiences on Arsenio Hall, while simultaneously vilifying the so-called “inner city” and its “superpredators” in a campaign of fear. Former mayor of New York Rudy Giuliani, meanwhile, was crediting aggressive law and order policies as having “cleaned up” the city: “There was a rising media culture that used Black people as an excuse to cut whatever social program they wanted to cut, and enforce whatever kind of policing they wanted to enforce.”

In contrast to the denigrating media narratives, Barrington’s community swaddled him in affirmation. At a young age, he found his truth: “I grew up in places where the majority of people looked like me, and everything in my life to that point reinforced my dignity, and my sense of self.” When his mother died in 1993, the artist was looked after by a network of aunties, and found solace in his cousins’ music. It was the golden age of hip-hop, a new, intimate era of storytelling that aligned with the events of his life.

“There was a one-to-one in terms of what Ghost was saying and what I was going through,” Barrington says, referencing the lyrics to All I Got Is You. “There are lines about ‘15 of us in a three-bedroom apartment’, and there were eight of us in a one-bedroom apartment. His mama passed away, and my mama passed away.”

The song ends with lines about looking up at the stars and looking forward to tomorrow. “If I didn’t have that song,” the artist says, “I would’ve had to find another way to cope with the situation I was in.”

History, Barrington has found, has had a longstanding habit of erasing the contributions of Black culture. He offers up the fact that Matisse had spent time in Harlem, cultivating relationships with black jazz musicians. “He was trying to paint jazz,” he says, both its rhythms and spontaneity. “You go to art school, and you never hear that.”

In 91–98 jfk–lax border, hip-hop fills holes in the historical record, recounting a contentious decade as Barrington remembers it. His recurring use of cement adds a sense of weight and permanence to stories that have been subjected to erasure. “Through making, I’m putting out ideas of what I think I know,” he says. “I might be right, I might be wrong.” He’s also adamant about his work always being accessible, and reaffirming his community: “It’s important that my family don’t feel dumb because they don’t know who Rothko is.”

Foregoing the traditional gallery dinner, Barrington opted instead to throw a small concert by one of his all-time favorite artists. (Blum & Poe co-founder Tim Blum says that he first heard that Ghostface would be performing at his gallery on Instagram: “You’ve really got to stick along for the ride with Alvaro”.)

Writing his own press release, the artist described the exhibition as “my thank-you to some of my heroes … Biggie, JAY-Z, and Lil’ Kim gave us the commandments to get fly and carry our heads high … [Ghostface] made us want to ground our souls and reach for the skies.” And where the 90s were filled with conflicting accounts, “The only real narrative was that we saved each other.”