How can we converse of those ‘frequent issues’, how, quite, can we stalk them,

how can we flush them out, rescue them from the mire wherein they continue to be caught,

how can we give them a that means, a tongue,

in order that they’re ultimately capable of converse of the best way issues are,

the best way we’re?

Georges Perec, Approaches to What

In 2021, I left Belarus not realizing whether or not I’d ever be capable of return. Among the many objects I believed to be among the many most valuable to maintain was a printed picture of my great-grandfather, Mitrofan Serebryakov’s funeral, relationship again to 1938. Right here it’s, proper in entrance of me, on my desk, after having travelled throughout 5 residences in two years. From the mist of the sepia, flickering by way of nearly a century of births and deaths, is a good-looking, bearded man mendacity peacefully in an open coffin, who I by no means knew. The deceased is surrounded by a gaggle of mourners, principally younger and middle-aged girls in an identical floral-lined headscarves (in all probability borrowed or bought particularly for this unhappy event) – all however one additionally strangers to me. The only particular person I acknowledge is a 14-year-old in one thing that appears like a tough, outsized man’s jacket – my grandmother to be, Maria.

Picture courtesy of creator, 2023

Now that I’ve this prolonged household by my aspect, I spend hours scrutinizing their severe faces, easy garments and reserved gestures. I can attain out to them, contact them. However does it imply I do know any of them higher? Reflecting on the difficult however nonetheless shut relations between wanting and touching, Margaret Olin would possibly suppose that I do: ‘Contact places individuals in touch with pictures; however as pictures move from hand handy they set up and keep relationships between individuals – or attempt to.’

From the late seventeenth to early nineteenth century, written and visible communication prolonged its attain, as migrating family members despatched each other touching ‘touchable’ proof of varied varieties: notes, handkerchiefs, locks of hair. And, as Raymond Williams acknowledges, images then joined this development, actually serving to hold households ‘in contact’ as soon as financial necessity had scattered them throughout the globe. Images had been valuable each due to their excessive manufacturing prices and the milestones they captured: the faces of curious newborns, solemnly dressed newlyweds, the calm ‘newly deceased’. I ask myself who my great-grandfather’s funeral picture was meant for. Had been there many family members in faraway lands to ship this photograph to? Did they finally get it? Was I additionally one of many addressees?

My teenage grandmother didn’t suspect that exactly ten years later she would transfer to a different nation herself and marry a man often called the son of ‘the American’. My great-grandfather, Ivan, was well-known in his village for having travelled to the US as a migrant employee, and having returned – a call, which within the Soviet Union, value him his life. He died in nearly the identical 12 months. Ivan Kozel was shot behind his head by Bolsheviks. He was 54 years previous, a father of 4.

Ivan by no means had a memento mori image taken of him after dying. Neither had been his family members notified. Only some months in the past, did we study his precise destiny, 86 years after the taking pictures. All this time, even for his grandchildren – my mom, her sister and brother – he remained a narrative, one unwillingly shared throughout household gatherings. In massive and small histories of our area’s kin and their nations, silence was a frequent visitor. Together with the household jewels, half-demolished village homes and previous images, we inherited suspicion, concern and the invaluable preciousness of contact.

Picture courtesy of creator, 2023

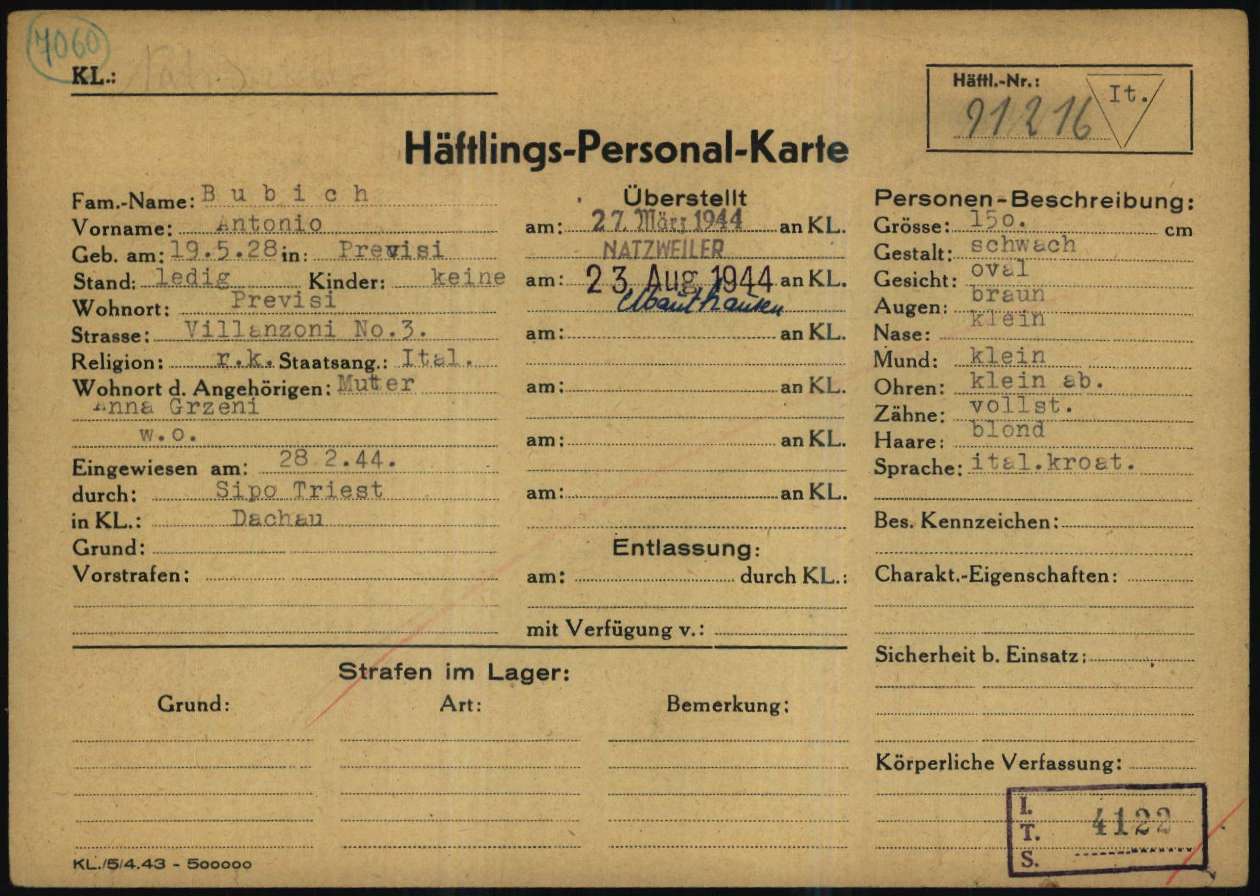

The sparkles of visible info I’ve managed to gather of sure ancestors is because of sheer luck. Others have left solely imprecise silhouettes, undiscernible contours, indicators I’m struggling to decipher. They lived on within the mementos of those that, of their flip, have additionally handed a very long time in the past, at instances alerting me to their presence. One such signal is the labor camp registration card of a 16-year-old Antonio Bubich: ‘prisoner quantity 91216’, whose SS inverted-triangle badge marked him as Italian.

{The teenager} was born in 1928, a peer of my paternal grandfather, Vasily, who escaped this brutal destiny. Our namesake was arrested in February 1944 and, over six months, witnessed three camps: Dachau, Natzweiler and Mauthausen. Meticulous measurements from 28 February to 23 August, made by the camps’ administrations, present that the teenager made a ten cm leap in top. Blond with brown eyes; state of enamel, ‘passable’; listening to and sight, ‘good’; occupation, ‘learner’ – classification was a routine follow for the Nazis. Deeming the representatives of different nationalities’ as ‘non-Aryan’ – and, due to this fact, of ‘inferior background’ – they actually handled individuals as objects in a horrendous catalogue of curiosities, labelled in varied levels of banality.

On prisoners’ arrival in focus camps, ID images had been taken. Francisco Boix, a Catalan inmate and camp survivor, labored within the Mauthausen camp administration’s images division. Understanding the crucial significance of visible proof, Boix risked his life to cover and protect round 2,000 negatives, which might play a major half within the conviction of Nazi battle criminals on the Nuremberg and Dachau trials. Maybe, being across the identical age, Boix had befriended the younger Bubich. Hopeful of studying extra, I filed a request to Mauthausen memorial web site archives and acquired a reply one week later.

‘Expensive Ms. Bubich,’ it learn, ‘Thanks on your enquiry. Sadly, we’ve to tell you that we should not have any pictures of Antonio Bubich in our archive. The prisoners had been certainly photographed and registered upon their arrival at Mauthausen. Nonetheless, these recordsdata had been systematically destroyed by the SS shortly earlier than the tip of the battle. Solely a few dozen pictures from Mauthausen have survived.’

I don’t know – and it’s unlikely that anybody can now show – if Antonio Bubich and I are associated. And, because the above e-mail makes clear, neither can I cherish the hope of ‘touching’ him photographically, searching for attainable similarities in our look, or speculating about his character traits. On 5 Might 1945, American troopers arrived in Gusen and Mauthausen and liberated round 40,000 prisoners. Was Antonio nonetheless alive on that day? Was he a type of ragged however free survivors seen cooking potatoes in a German Military helmet? Did he reunite together with his household in ‘Previsi’ – the in all probability misspelt identify of his hometown that I didn’t find on a map of North Italy? Did he make it?

Registration card. Picture courtesy of creator

With out proof, I’ll by no means have solutions to those questions. ‘Made attainable by context, pictures are greater than context,’ writes Olin, ‘they contact one different and the viewer. They substitute individuals.’ She was proper. Images do substitute individuals, however so too does the void. Generally, silence can converse – we simply must study to pay attention.

Among the best-known documentary artwork initiatives geared toward reminiscence preservation can be linked with contact: Stolperstein, the German for ‘stumbling stone’, metaphorically that means a ‘stumbling block’, refers back to the brass plates embedded in paving slabs passers-by are supposed to return throughout coincidentally and thus pay extra consideration to. As of December 2019, about 75,000 such blocks with inscribed names and life dates of victims of Nazi extermination or persecution had been put in in additional than 1,200 cities around the globe. The idea, conceived by German artist Gunter Deming in 1992, would possibly provocatively be linked to the antisemitic phrase, as soon as widespread in Nazi Germany, stated when by chance stumbling over a protruding stone: ‘A Jew have to be buried right here.’

Stolpersteine will not be really easy to detect. If big monuments are designed to impress when noticed from distance, little brass plaques emphasize the ‘smallness’ of human lives and, if you wish to study extra about them, you have to be humbled and lean down. It is just by the aware discount of distance, preceded by the readiness for contact, the need to get to know somebody’s previous – your personal, even – that one realizes the lifetime of one other particular person can be massive.

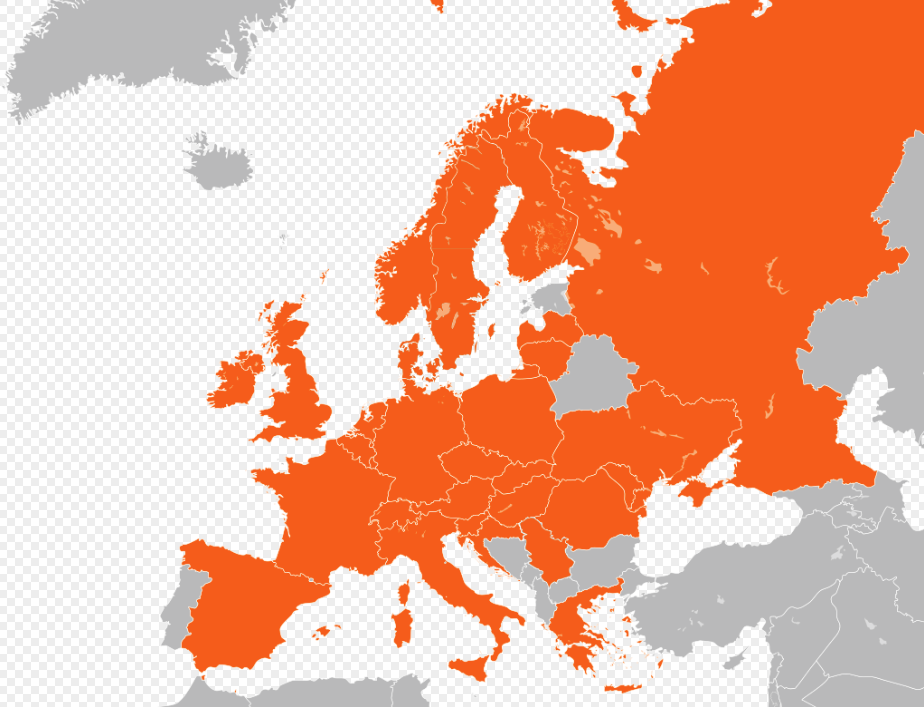

Not each nation that has confronted mass murders, repression and torture is able to lean down and put effort into processing trauma. Recognition of guilt needs to be adopted by the following, much more difficult step: acceptance of accountability. Russia, a state that destroyed greater than three million of its personal individuals in its Soviet previous, doesn’t need to admit this reality even a century later. A fast look on the Stolpersteine map helps perceive the Kremlin’s amnesia: Russia, although colored orange, solely has two memorial stones put in inside its huge space.

The ‘Final Handle’ grassroot initiative impressed by Deming’s idea hasn’t prompted a lot enthusiasm amongst sure state our bodies. Memorial plates have ended up being dismantled by native administrations or anonymously vandalized in Russian cities. Police have refused to analyze the circumstances. Makes an attempt to silence reminiscence can’t be categorized as crimes, can they?

Overview of nations the place Stolpersteine have been put in.

Cirdan – Personal work, based mostly on File:Clean map of Europe 2.svg by Person:Nordwestern. Picture by way of Wikipedia

The photograph sitting on my desk is a luxurious. Other than my teenage grandmother within the picture of my great-grandfather’s funeral, there may be one different particular person I do know – myself. I’m not ‘there’ however am ‘current’. From my 2023, I can contact their 1938.

I’m doing my greatest to listen to the touching reminiscences within the choir of talking voids.

In affiliation with ICORN, the place Olga Bubich is at present a fellow.

Supply hyperlink