In 1988, no one in France took the hip-hop movement seriously. It was the rec-room era. JoeyStarr and Kool Shen were just two kids from Seine-Saint-Denis, the 93rd ward, a neglected tract of housing projects on the northern outskirts of Paris. One black, the other white, they shared a love and a talent for breakdancing and got together practising moves in bleak lots and house parties. They started crews and listened to Doug E Fresh, Masta Ace, Grandmaster Flash, and Marley Marl. DJs played the breakbeats looped over jazzy horn riffs, cats sported Kangol hats and Cosby sweaters, and they tagged the walls of the city with their calling card: NTM, an acronym for “Nique Ta Mère” (Fuck Your Mother). There were no labels, no official concerts or shows, and the only airplay was after midnight on Radio Nova, a station dedicated to underground and avant garde music, created and directed by French countercultural hero Jean-François Bizot.

I was at a house party in a spacious bourgeois apartment somewhere in the 16th arrondissement when I first heard DJ Cut Killer’s track La Haine, better known by its infamous refrain “Nique la police” (Fuck the police). I hadn’t yet seen the film La Haine, which made the song famous, and remains arguably the most important French film of the 90s. I was at a boum, slang for a teenage house party and a tradition of Parisian coming of age that involves a great deal of slow dancing and emotional espionage. Sophie Marceau immortalised it as a mesmerising ingénue in the greatest French teen romance ever produced, La Boum. But I wasn’t dancing with Sophie Marceau. I was dancing with Caroline.

A young dude interrupted Ace of Base and popped in a cassette he had brought in his jacket pocket. The party came to a jarring halt as everyone looked at everyone else trying to figure out what to do. The shock of hearing someone actually say “fuck the police” and repeat it again and again stunned me. The owner of the tape was bragging about how he got it. How it was banned, and you could only find it “underground”. This turned out to be true, though I didn’t believe it at the time. Caroline insisted she was impressed, but her body was limp, her eyes vacant. The song made a big impression on me. Even without fully understanding everything on the record, the exhilaration of open rebellion was palpable. Over an onslaught of breaks and scratches a voice shouted: “Who protects our rights? / Fuck the justice system / The last judge I saw was as bad as the dealer on my corner / Fuck the police / Fuck the police!” KRS-One samples collided with a looping of Édith Piaf’s Non, Je Ne Regrette Rien. We understood the symbolism perfectly. The difference between Sophie Marceau’s world and ours was the existence of the ghetto as an undeniable fact. The party was over.

I arrived in France in 1992, the year the Maastricht treaty creating the European Union was signed and Disney opened its first European theme park just outside Paris. I was still a kid and spoke not a word of French. It was not going to be easy figuring out how to grow up as a black American in Paris. The skin game was complicated. I was too light-skinned to be from Senegal, but dark enough to be from Algeria or Morocco. Declaring my Americanness, I soon learned, was necessary for avoiding a certain nastiness of tone specially reserved for the postcolonial subject. On the other hand, as an expatriate American at an international school, I was moving in bourgeois circles. Money cushions social realities and creates a haze of similarity among peers until you get to around sixteen, the age in Paris when you start to roam the city alone, have your first real crush, and learn how to roll a cigarette while waiting for the Métro.

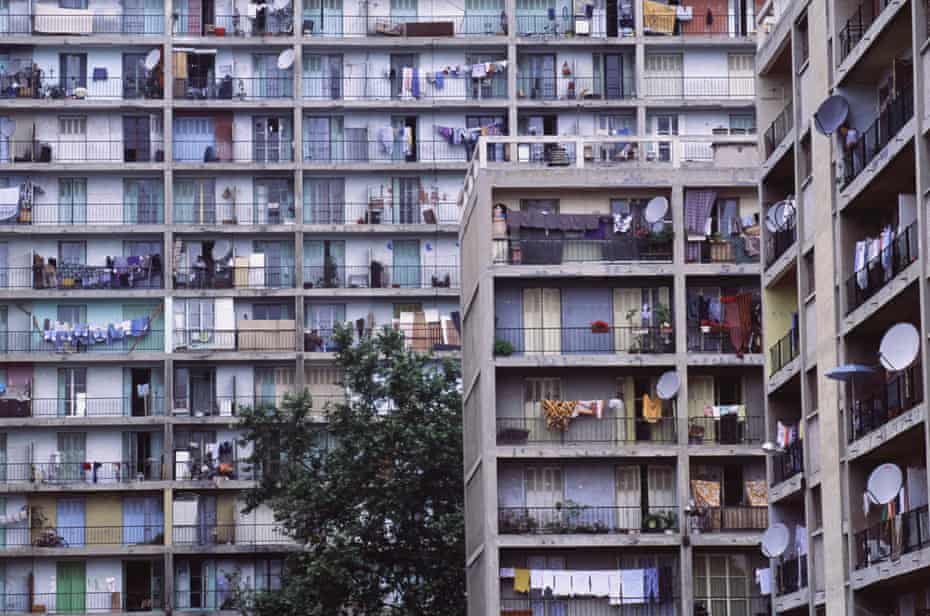

The peripheral zone known as the cités or banlieues was terra incognita to me at that point. Nobody I knew had ever been that far off the map. You glimpsed the banlieue from the train, on your way to the countryside or the airport; its inhabitants lived there, trapped beyond the city walls, as though feudal relations had never really collapsed in the capital of the French Revolution. I did know the symbol for that space: HLM, an acronym signifying a set of social-housing block towers grouped in pods of dreary urban sprawl. They were built during the years of the post-second world war economic boom the French call Les Trente Glorieuses (The Glorious Thirty), when ex-colonial immigrants were imported into the republic as cheap labour for a country still rebuilding from the catastrophe of the war. The HLMs were exalted for their modern incarnation of Le Corbusier’s ideal of sleek “towers in a park” and satirised for their sterile futurism by Jacques Tati in his classic 1967 film Playtime. France has always had a rather anxious attitude towards modernisation.

But the architects of the utopian HLM did not account for the social and political effects of racial and historical prejudice. By the 80s the boom had petered out, and the cheerful attitude toward cheap immigrant labour soured into an austerity-driven desire to push the immigrants and their children – born with French citizenship – back out. If not out of the country altogether, then out to the social housing blocks on the fringe of the cities – out of sight.

Resistance began in language. The French state has an obsessive attachment to the purity of the tongue. It maintains an academy devoted to policing grammar and ratifying vocabulary. In the early 00s, it declared that email would henceforth be called courriel, a derivative of courrier (mail). To this day all government employees have to send courriel. The rest of the country sends mail. Against this stodginess, the banlieue gelled around an outsider culture and generated its own idiom. “Verlan” is a play of word-flipping, where the first and last syllables of a word in French are inverted (femme becomes meuf, l’envers becomes verlan, etc) By importing words from American English and, most of all, Arabic words from across the Maghreb, the outsiders created their own counter-French, the creole of the ghettoised.

And yet, at least in the world of music, it seemed the newcomers would have to bend to the rules of French culture rather than the other way around. That strategy produced the first crossover hip-hop star, MC Solaar. It was Solaar who single-handedly established the literary imperative in French rap on his first album, Qui Sème le Vent Récolte le Tempo. Solaar made a point of demonstrating his fluency beyond the street, taking on a hybrid troubadour-griot persona that situated him just within the orbit of chanson française, provocatively making himself heir to the likes of Jacques Brel, Georges Brassens and Serge Gainsbourg. In one of his singles he raps, “L’allégorie des Madeleines file, à la vitesse de Prost” – combining an allusion to Proust’s madeleine with a nod to Alain Prost, France’s Formula One racing hero of the 90s.

Qui Sème le Vent was one of the first CDs I ever bought. The first couple of songs, heavily influenced by Gang Starr, were snappy enough. The second half of the album was less appealing, a half-baked dub collage. But smack in the middle was the track that would make Solaar instantly famous, a love ballad called Caroline. I listened to that song over and over again. It was cheesy and sentimental and yet undeniably a feat of lyrical virtuosity. It evoked everything you could feel about first crushes all at once. The whole album still sounds in its very grain “old school”, a term that has come to hover as a halo over a golden age of hip-hop bathed in what from our current standpoint looks like a shocking and enviable innocence. But there really is a greenness in Solaar’s soft-spoken, almost-whispered delivery that connects with the green of Parisian sidewalk benches, where first cigarettes and first kisses imprint their weightless marks of identity. Solaar had the perfect pitch at the perfect moment: the overwrought saxophone riffs, the fanciful turns of phrase, the dub connection, the long Proustian sentences carrying over 16 bars in a song. But it was for these same reasons that his artistry became instantly outdated, an artefact of nostalgia, something that could not keep in step with the cultural supercollider that hip-hop was forcing down the line.

Fila sneakers, Lacoste caps, Sergio Tacchini tracksuits, one sock rolled up, a fur-lined bomber jacket, shaved heads, bum bags for holding sticks of hashish the size and colour of a caramel bar wrapped in tinfoil, tricked-out Yamaha scooters. By the mid-90s the profile had been established and the term racaille had entered the popular lexicon to describe a disaffected young man from the banlieues. Their arrival within the city walls was turbulent and disturbing. For the first time I was faced with a definitive “other”. We knew that they didn’t belong in our world any more than we belonged in theirs. There was no question of integration. And so it always seemed, at least to me, that everything was contested in the only public spaces we shared – in the public transportation system. I can never entirely dissociate racailles from the RER commuter trains, with their acrid, low-grade plastic smell, the pallid lighting of underground transfer halls, the whine of the electric motors and the fear of police patrols with German shepherds.

There were acts of violence, some symbolic and others very real. You readied yourself for tense showdowns on empty platforms, you dreaded menacing whistles directed at your presence, and you practised running up flights of stairs to the street. Entire areas in central Paris – Les Halles, Beaugrenelle, and even the Champs-Élysées – became off limits, even in broad daylight. Of course there was a complicating factor, namely that you also sought the same guys out to buy hash and weed. Dealers dropped by the high school on scooters to take numbers and chat about video games. But sometimes they were the same ones who got a crew together and jumped you for your wallet or your mobile phone.

For most people, even in France, the idea of Paris is still heavily indebted to figments of a romantic Belle Époque strain, whether coloured like a Toulouse-Lautrec dorm-room poster, lifted from a black-and-white photograph of May 68, or raised to an arch postcard fantasia, as in Woody Allen’s Midnight in Paris. Frenchness in this sense seems incompatible with hip-hop; even the language itself seems somehow unfit for rapping. To put it bluntly, this vision of Paris does not include immigrants of colour. Despite my being on the bourgeois side of the class line, the Paris of colour, of difference, could never be invisible to me. It troubled me, made claims on me that I couldn’t fully understand. Perhaps it bridged my own invisible loneliness. But it wasn’t just me, or people like me. In our generation you had a choice: it was Suprême NTM or Daft Punk. And the choice felt deeply existential. Certain people would never be friends because of it. Plenty of kids chose to tune out the world and immerse themselves in the pill-popping scene of techno, house and electronica. Caroline was one of them. We never openly admitted why we grew apart. But it was there all the same. She wanted to go clubbing at the Rex on Saturdays; I tried ecstasy and decided it wasn’t for me. From there it was two roads peeling away for ever.

The club kids looked to London. If you were hip-hop, you turned to the US. The most powerful impulse came from the west coast, as Dr Dre and the G-Funk era made their way across the Atlantic. Groups like Reciprok and Mellowman suddenly had the sounds of summer, and for the first time in its history, France had summer jams that weren’t cheesy pop tunes à la Claude François. Tracks like Libre Comme L’air (featuring a guest appearance from Da Luniz), Balance-toi, and Mellowman’s La Voie du Mellow were saturated with warm P-Funk chords usually heard whining out of low-rider trunks in Inglewood and Oakland.

In Paris, the king of this sound was Bruno Beausir, AKA Doc Gynéco. More than any other French rapper, Gynéco incarnated the ideal of adolescence. Laid-back, good-looking, smart, fresh gear, the guy who gets all the girls, has the best comebacks, has the best weed and wears the latest sneakers. He made having as your primary interests sex and getting high look really good. He sported a tight, just-got-back-from-the-French-Open look: clean designer polo shirts, headbands under his natty dreads.

On the cover of his 1996 album Première Consultation, Gynéco slouches under a big afro, showing off creased slacks and all-white Adidas shoes. He took the game up a notch. His rhymes were funnier, his references broader but also more popular: football, politicians, soap-opera starlets – in other words, television. His biggest hit, Nirvana, is a quintessentially adolescent expression of ennui. “The hottest girls / You can have them / I’m tired of all that,” he complains. “Tired of the cops / Tired of the gangs / Tired of life.” In the refrain he gives a dopey lament about how he’d rather shoot himself in the head like Pierre Bérégovoy, François Mitterrand’s prime minister, or go out fast like Ayrton Senna. You can’t be too serious when you’re 17, as Rimbaud says.

Just as hip-hop in the US was concentrated for a time around east v west coasts, the hip-hop scene in France quickly became oriented around two distinct and rival poles: Paris and Marseille. In Paris, the three letters that mattered were NTM. In Marseille, they were IAM. The latter were latecomers, but with their album L’Ecole du Micro d’Argent, the Invaders Arriving from Mars (short for Marseille) blew up instantly. IAM’s rappers styled themselves after the Wu-Tang Clan and their tracks reflected a close study of RZA’s production. In the mid-90s, there was even a glimmer of hope for a transatlantic hip-hop empire, as rappers from New York collaborated with their French counterparts with fascinating, if somewhat mixed results. Like Wu-Tang, IAM presented themselves as a warrior horde. They took the names of Egyptian kings and kung fu masters: Akhenaton, Shurik’n, Khéops, Imhotep. For a listener from Paris, there was also the peculiar flavour of the southern accent, with its long vowels and the insistence on the importance of Islam and political solidarity. But the rappers of IAM transcended geography and race; unlike their American counterparts, their case was built on a deeply entrenched class consciousness.

In the quartiers nord of Marseille, the race line is blurry at best. Its residents are African, Arab, Creole, but also southern Europeans, particularly Portuguese, Corsicans and Italians, of which Akhenaton (Philippe Fragione) is a descendant. And most of the hip-hop generation comes from families that are likely to be mixed. In a port city like Marseille, though, the neoliberal factor is more readily evident than anything racial. What matters is inequality. The costs of the shadow economy are high, and the violence that comes with trafficking and corruption is unavoidable. In songs like IAM’s Nés Sous la Même Étoile, drug money and the nihilistic culture it fosters are denounced for destroying youth, equality and promise. The answer in the hook is bitter: “Nobody is playing with the same cards / Destiny lifts its veil / Too bad / We weren’t born under the same star.”

There’s an argument to be made that no French rapper has ever matched the verbal dexterity and range that you can find in the verses of classic American MCs like Nas, Biggie, Tupac, GZA or Rakim. I mean that real cutting showmanship, the dazzling shell fragment that makes American rap so pungent. In part this is due to the fact that American rappers use verbal ingenuity as a kind of evasive tool, enlisting black vernacular to stay one step ahead of accepted, assimilated “white” discourse.

But the runaway success of songs like IAM’s Petit Frère or NTM’s Laisse Pas Trainer Ton Fils demonstrates that in France there is no schism between alternative rap and the commercial mainstream current. There is no French equivalent of artists like Immortal Technique, Mos Def or Talib Kweli; IAM and NTM never set out to be socially conscious. This has given French hip-hop artists an intellectual and emotional licence that can be enormously compelling. It’s why the NTM rappers can growl like DMX and at the same time talk about how a father needs to love and listen to his son. On the hook of their biggest hit single, Kool Shen raps, literally translated, “They shouldn’t ever have to look elsewhere to find the love that should be in your eyes”. You can’t find a line quite like this anywhere in the Def Jam catalogue. In the big leagues of US rap, only Tupac could convincingly deliver this kind of sentimental sincerity, and even then it came encased in the heavy armour of thug life.

Suprême NTM was always a much harder outfit to classify, perhaps because they have been in the game the longest and are also the truest reflection of hip-hop in France. They embodied all the contradictions, circumvented all the traps. Of all the music produced in France over the last two decades, their contribution remains perhaps the most important, the most influential and the most popular among young people across all social categories. What JoeyStarr and Kool Shen gave us was the nearest possible translation of freedom – the smack of liberty that they copped by listening to the best records from the golden era of American hip-hop. They weren’t flowery like Solaar, or preachy like IAM, or above the fray like Doc Gynéco. Somehow, NTM nailed the anger and the cool in the same note, bypassing categories like Miles Davis, voice in command like Rakim. They would break out dancing at shows, something virtually impossible to imagine in the world of US hip-hop, where the role of the MC has remained strictly verbal. They defined an entire generation and gave it a conscience. There’s no way to give an account of Paris at the turn of the millennium without them.

NTM were never political in the sense of pushing a message. But they effortlessly controlled the terms of debate. The establishment attempted to paint them as dangerous and cop-hating hooligans, but one of their biggest singles, Pose Ton Gun (Put Down Your Gun), hauntingly backed by a Bobby Womack sample, became a national anthem to nonviolence. Yet they murdered whole institutions in the space of a verse. They relentlessly exposed the hypocrisy of the French establishment, the Pasqua-Debré immigration laws, censorship, political corruption and so on. When a television interviewer asked JoeyStarr about the violence of his lyrics, he corrected her. “It’s not violence,” he said, “it’s virulence.” No political actor or social commentator has been as articulate about the current social impasse in France.

With time, the rap game in France has evolved along the same lines as everywhere else. The new artists attempt to use Auto-Tune. They splurge on knock-off versions of Hype Williams videos, with interchangeable Miami Vice sports cars and booty girls; they abuse a plethora of mistranslated cultural references. Sefyu, an heir apparent to the hip-hop game in France today, is a morose and standoffish figure who refuses to show his face in videos and is more interested in coordinating his sneakers with his outfit than in paying for a decent beat. In a bizarre turn, Doc Gynéco veered politically to the right, infamously cheering Nicolas Sarkozy’s rise to power and reinventing himself as a cynical court jester to the elite. He told people he had grown up. But really, he’d just shown us what he was all along: a jerk.

When I look at the contemporary situation, I confess it’s hard not to get depressed. Nothing seems fresh any more; nothing seems green with life or genuine yearning. Then again, maybe I’m just older.

Hip-hop is an adolescent genre of music. Between the lines you can plainly see attempts to tackle critical issues: social inequality, sex, religion, mortality, boredom, fear. But, ungainly and awkward, it indulges in the most ridiculous immaturity. Still, the stupidity of adolescence is not without its rush, its exhilaration. Freshness has its place. The music of our youth is tinged with a special effervescence. It is imbued with meanings we can only barely articulate, coloured with feelings couched in half-remembered conversations, in old friends and half-forgotten crushes, stored amid all the whirring dynamos of the unconscious. Maybe this is why, on a personal level, French hip-hop is so easy for me to forgive, even though it still has a kind of embarrassing stigma. French hip-hop? Really? Well, yes. I actually can’t listen to JoeyStarr shouting out, “Saint-Denis Funk Funky-Fresh!” without cracking a huge smile. Saint-Denis, c’est de la bombe bébé!

But emotional immaturity doesn’t imply historical insignificance. If we could borrow Zola’s glasses and look down on the city of Paris to take stock of the last two decades, what would instantly stand out is a series of kaleidoscopic collisions seething with energy and frustration: the banlieues, the stalemate of the ghetto, the restless periphery of the marginalised sons and daughters of the postwar immigration and their uncertain fate. Hip-hop has registered and encoded this historical narrative and expressed it in a native tongue.

Tout n’est pas si facile,

Les destins se séparent, l’amitié c’est fragile

Pour nous la vie ne fut jamais un long fleuve tranquille

Nothing is so easy,

Destinies separate us, friendship is fragile

For us life was never a long tranquil river

When I hear Kool Shen rap on lost friendships it pulls me back to a certain time and a certain place. It wasn’t easy for anyone. But we were all there and hip-hop was our music; and because we were adolescents it was also our conscience. Now when the beat flows and I nod my head, the grain of Kool Shen’s voice still has the power to evoke certain truths. It’s hard coming up in the world. You have the best of times and the best of friends. Then things fall apart. Or maybe things just change. You grow older and you don’t always figure shit out. Ralph Waldo Ellison defined the blues as “an impulse to keep the painful details and episodes of a brutal experience alive in one’s aching consciousness, to finger its jagged grain”. Hip-hop is steeped in this sensibility. The verbal dexterity, the allusive sampling, the poses and the braggadocio, they all amount to one underlying message: I rock the mic – life’s a bitch, and then you die. It’s about snatching good times from the teeth of times that couldn’t be worse. Life is not a tranquil river. It’s like that, and that’s the way it is.

This is an edited extract from Jesse McCarthy’s essay collection Who Will Pay Reparations on My Soul?, published by Liveright on 30 April