John Brett, 1856. Picture: Tate

John Brett, 1856. Picture: TateA brand new exhibition that paperwork the affect of the Industrial Revolution options a number of 1800s artists, writers and thinkers as they started to seize the transformation of the surroundings.

Who knew what, and when, from the beginning of the nineteenth Century on, in regards to the affect of industrialisation and using fossil fuels on the surroundings? A brand new exhibition on the Huntington Library, Artwork Museum and Botanical Gardens, simply exterior of Los Angeles, entitled Storm Cloud: Picturing the Origins of Our Local weather Disaster, helps to hint the scientific, historic and creative file again to the beginnings of the Industrial Revolution.

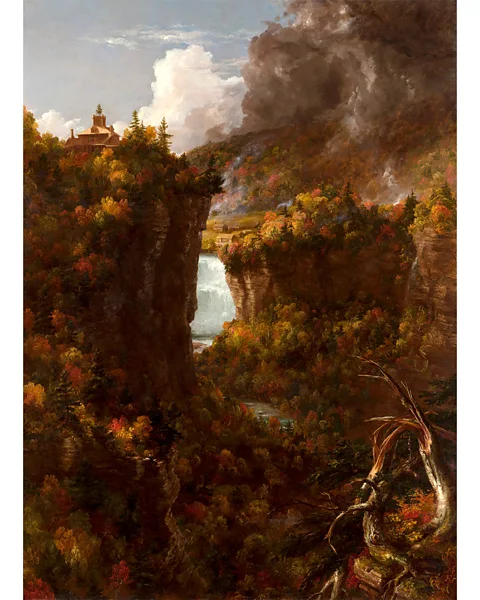

One early witness to the altering hues of the countryside’s as soon as clear skies and untouched panorama was the British-American painter Thomas Cole (1801-1848). In 1839, he travelled to Portage Falls on the Genesee river in upstate New York to doc the chic vistas, rocky cliffs and ample foliage surrounding the deep gorge by means of which the river flowed. Cole’s activity, commissioned by the New York State Canal Commissioner, was to protect in oil paint the view about to be destroyed by the forthcoming building of a brand new canal that will construct on the success of the Erie Canal, which had opened in 1825.

Cole, who was identified for his monumental landscapes, produced a giant-sized imaginative and prescient of nature’s splendour in a canvas that stands 7ft (2.1m) tall and 5ft (1.5m) extensive. Vibrant autumnal foliage frames the dramatic vertical view of the gorge and the waterfalls flowing past. However this Eden was not pristine. Atop the cliff on one aspect of the gorge sits a picturesque lodge; simply throughout, on the alternative cliff, on degree floor apparently carved out from the wild development dominating a lot of the website, lies a housing camp for the canal employees.

Thomas Cole, ca 1939. Present of The Ahmanson Basis

Thomas Cole, ca 1939. Present of The Ahmanson BasisDifferent omens of business’s persevering with encroachment on nature seem within the type of darkish clouds in agitated movement above the gorge. Under the gorge, simply past an undulating creek, lies the gnarled, twisted remnants of two lifeless bushes. And amidst all of it, Cole himself seems as observer and chronicler to the pending lack of the pure panorama in a tiny self-portrait that depicts him sketching the scene whereas seated in a virtually hidden leafy bower. As if the portray has not sufficiently revealed his sentiments, his phrases additionally seem on a gallery wall above: “The ravages of the axe are every day growing – probably the most noble scenes are made desolate.”

Cole’s majestic imaginative and prescient is just one of the roughly 200 gadgets – together with work, scientific illustrations, uncommon books, images, manuscripts, drawings and textiles – that doc how as soon as clear skies and untouched landscapes turned reworked by the Industrial Revolution. We see how, from the 1780s on, the engines of business actually took up steam. Rising numbers of coal-burning furnaces have been quickly fuelling an increasing number of factories and mills, with their merchandise usually then transported to metropolis markets by newly constructed railways and re-channelled waterways and canals.

Philip James de Loutherbourg/Science Museum/Science & Society Image Library

Philip James de Loutherbourg/Science Museum/Science & Society Image LibraryAmongst others, French artist Philippe Jacques de Loutherbourg (1740-1812) additionally chronicled the metamorphosis from pastoral scene to industrial office. In his 1802 portray, The Ironworks, Coalbrook Dale by Evening, the fiery night-time scene of the ore-smelting works seem as frightful as a Halloween cauldron.

In the meantime, scientists have been additionally observing atmospheric modifications and climate deviations, and the exhibition tracks these findings as properly. In 1833, British chemist and meteorologist Luke Howard (1772–1864) printed his 700-page research, The Local weather of London. His examination of a decade’s value of London’s every day temperature readings, water ranges, rainfall and wind route led him to conclude the existence of what he referred to as an city “warmth island” impact. The accompanying exhibition label explains the method behind Howard’s findings: “As a result of buildings, roads and different city infrastructure soak up and re-emit the solar’s warmth, cities are typically a number of levels hotter than much less developed areas with bushes and our bodies of water.” Howard additionally famous that such modifications in temperature coincided with a phenomenon he named “metropolis fog” – which at the moment we name smog or air air pollution.

‘Reverence for nature’

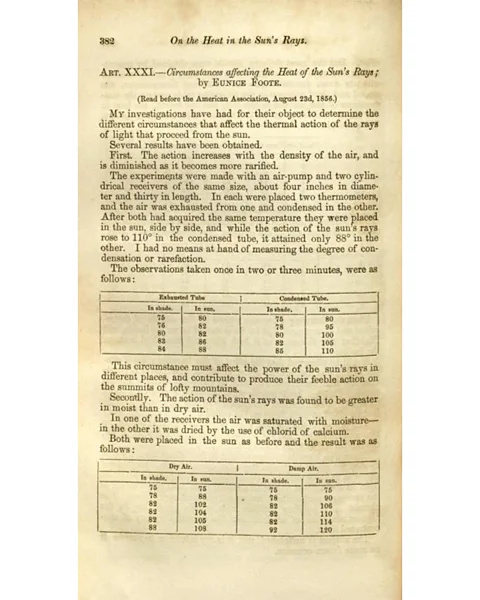

The exhibition additionally highlights the pioneering environmental work of the lesser-known US scientist, inventor and ladies’s rights advocate Eunice Newton Foote (1819-1888), whose 1856 publication Circumstances Affecting the Warmth of the Solar’s Rays in The American Journal of Science and Arts, demonstrated that carbon dioxide (CO2) trapped warmth, a climate-altering course of she referred to as the heat-trapping impact. Hers was the primary recorded experiment displaying the affect of CO2 emissions on what we now name local weather change. However Foote’s analysis was largely missed. As an alternative, British physicist John Tyndall (1820-1893) obtained credit score for the discovering in a research printed three years later. It stays unclear whether or not Tyndall was acquainted with Foote’s work.

Writers just like the US creator and naturalist Henry David Thoreau (1817-1862) had additionally begun gathering his personal measurements of fixing river depths and detailed notations of flowering and hen appearances close to Walden Pond in Harmony, Massachusetts, the place he lived.

But it surely has solely change into obvious in latest a long time simply how important his observations can function comparability factors between then and now. Witness on show, for instance, Thoreau’s methodical charting of temperatures over the seasons at Walden Pond. Extra not too long ago, local weather change biologist Richard Primack has detailed in his e book, Walden Warming, the numerous flowers that are actually blooming earlier at the moment than in Thoreau’s time, because of rising temperatures.

Whereas Thoreau’s information at the moment is usually getting used for functions of comparability, the creator did himself specific alarm on the injury attributable to human intervention, says Karla Nielsen, exhibition curator and Huntington’s senior curator of literary assortment. On his walks, “He would discover that the Merrimack’s course was being modified because of the factories on the river,” she tells the BBC, as a result of the dams inbuilt reference to the mills disrupted the water’s pure, seasonal circulation.

Biodiversity Heritage Library – The American Journal of Science and Arts

Biodiversity Heritage Library – The American Journal of Science and ArtsAs Melinda McCurdy, The Huntington’s curator of British artwork and co-curator of the exhibition tells the BBC: “We’re not saying that local weather change was recognised as such within the nineteenth Century,” However on the identical time, she says, individuals have been starting to: “recognise that the Industrial Revolution and human actions” have been altering the surroundings.

Maybe satirically, these rising inklings of the potential injury being attributable to industrialisation coincided with an growing reverence for nature, fostered by Romantic poets equivalent to William Wordsworth, a few of whose early editions are additionally on show. Or maybe this newfound enthusiasm was fed a minimum of partially by the expansion of cities, the place many former rural inhabitants now lived, discovering work within the burgeoning realms of business. Guidebooks (a number of of that are on show within the exhibition) proliferated as travellers ventured into the countryside to reconnect with nature.

Such attitudes fostered the environmental consciousness of Thomas Cole, amongst others. However it might have additionally influenced some artists to not explicitly present the modifications going down within the surroundings. The British artist James Ward (1769–1859) in 1805, as an example, matter-of-factly portrayed the panorama of the main industrial space close to Swansea, south Wales, popularly referred to as Copperopolis, as if the darkish clouds of smoke arising from the manufacturing facility chimneys had all the time been there.

In a considerably comparable vein, some critics now argue that the work of the nice British artist John Constable (1776-1837) current usually idealised views of the Sussex countryside with which his work is so carefully recognized. These are the lands by means of which the Stour River ran, the place he had grown up and to which he remained hooked up all through his life. On show we see one in all his well-known 6ft-long landscapes (usually referred to as his six-footers), View on the Stour Close to Dedham, 1822. It’s an inviting pastoral scene wherein riverbank greenery frames males at work steering their barges by means of the water – and in addition directs viewers’ eyes to a wood bridge within the distance and past that, the church tower of the city of Dedham.

John Constable, 1822. The Huntington Library, Artwork Museum and Botanical Gardens

John Constable, 1822. The Huntington Library, Artwork Museum and Botanical GardensActually, the portray reveals off Constable’s exceptional eye for element; his many hours of commentary spent sketching clouds had taught him to render cloud formations with scientific exactitude. However the realistically rendered scene doesn’t inform the complete story, says McCurdy. Over the course of Constable’s maturity, British landscapes might have been within the strategy of being criss-crossed and torn up by railroads and factories, and rivers have been being changed into simply navigable canals. However the scene that he presents, McCurdy says, is one “seen by means of the nostalgic lens of childhood… whereas portray it as an grownup”.

In stark distinction, the British artist and critic John Ruskin (1819-1900) decried the coal-generated soot and smoke darkening the previously clear skies as “The Storm Cloud of the nineteenth Century”. That was the title he used for 2 public lectures he gave in 1884, and his phrases resound all through the exhibition, which prominently shows his exhortation describing the storm cloud as wanting as if “it have been product of lifeless males’s souls”.

The exhibition reveals slide projections derived from drawings by Ruskin which he utilized in his lectures, Thunderclouds, Val d’Aosta (1858) and Cloud Research: Ice Clouds over Coniston (1880), in addition to an 1876 watercolour titled Sundown at Herne Hill by means of the Smoke of London. In these works, viewers can see the darkening transformation of the skies that Ruskin had meticulously traced in his diaries and drawings by means of the years. What we now know as air air pollution he referred to as a “plague-wind”. Ruskin had hoped to stoke concern together with his lectures, which have been among the many earliest works to explicitly focus on human-made local weather change, but it surely’s unclear what distinction his outrage made. “I do not know of any particular studies of reactions to the lectures,” McCurdy says.

John Brett, 1856. Picture: Tate

John Brett, 1856. Picture: TateNonetheless, London’s pea-soup thick, discoloured air was by then no secret, with writers equivalent to Charles Dickens and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle steadily alluding to the town’s unhealthy and visibility-limiting yellowish fog, as did quite a few cartoons in Punch. And in 1891, British scientist BH Thwaite (1858-1908) printed a cautionary pamphlet titled The London Smoke Plague. In it, he contended that London’s coal-induced poor air high quality was as lethal because the Seventeenth-Century Nice Plague, accounting for the mortality of 4 per cent of London’s inhabitants over two weeks in 1886.

By the beginning of the twentieth Century, numerous teams advocating cleaner air had begun forming. Certainly, British artist RW Nevinson (1889–1946), whose 1916 hazily greyish pastel, From an Workplace Window, seems within the exhibition, himself helped discovered The Brighter London Society.

However the storm cloud of the nineteenth Century did not stop, which is why the exhibition’s strongest and poignant work might be the imposing icescape Glacier of Rosenlaui by the Ruskin-influenced British artist John Brett (1831-1902). A broad, vivid stream of white tinged with blue emerges, and travels upward from a mattress of boulders and stones of various sizes, in the end resulting in a heaven-like mist of mountains and clouds, and maybe past time itself because it reaches the portray’s high. What higher image of pure splendour than this pristine glacier, so thickly ensconced by layers of snow and ice, that it is virtually unimaginable to think about this frozen mass retreating, melting, dissolving as temperatures rise.

Storm Cloud: Picturing the Origins of Our Local weather Disaster is on the Huntington Library, Artwork Museum and Botanical Gardens, San Marino, till 6 January 2025.

Supply hyperlink