Springsteen, a fairly apolitical cultural populist at that point in his career, fought off the opportunistic embrace of both Reagan and Mondale. But the campaigns of both men well understood that the failure of Springsteen’s anthem to deliver any intelligible political message was, in fact, the basis of its mass appeal. And as is the case with any document bearing witness to white-inflected grievance, its own identitarian agenda was pretty much hiding in plain sight:

The campaigns understood … that, whatever their candidates would or wouldn’t do for the working class, the white worker and the Vietnam vet meant something else to white men who identified as neither. The insecure white worker of a Springsteen song signified for white men, including most of all middle-class nonvets, that they had their own hard-luck stories, that they had suffered in the wake of civil rights, feminism, and the Vietnam War. The Reagan and Mondale campaigns found in Springsteen, with the subtle mutable racial meaning of his songs, a rare figure of consensus in the emerging culture wars. Who wouldn’t vote for Bruce?

Neither subtlety nor mutability was a going concern for Sylvester Stallone, whose blockbuster 1985 film, Rambo: First Blood Part 2, brought the image of the Vietnam vet back to its jingoistic Cold War roots. Stallone’s title character is dispatched back to Vietnam on a POW rescue mission and delivers his signature catchphrase in reply to the officer briefing him: “Sir, do we get to win this time?” The movie script also goes out of its way to give the character of Rambo a new ethnic identity that hadn’t been referenced in the franchise’s debut film or in the novel that formed the basis of the Rambo series: He’s made half–Native American. As Darda notes, Rambo’s manufactured Indigenous backstory gave a character played by a white actor a way to co-opt a narrative of discrimination: “The white ethnic revival had made white minorities the most American thing of all.… In the 1980s, that meant a white actor starring as a half-Indian soldier—a minoritization that, as simulated rather than embodied, allowed all white men to see themselves reflected in it.”

Much the same simulacrum of authenticity altered the hallowed status of veteran-ness in the film. When one of Rambo’s overseas handlers—a feckless government bureaucrat based in Thailand—turns out to be lying about his military service record, Rambo more or less shrugs it off. In his debriefing session after the mission, he explains that he only wants “what they [the POWs] want, and every other guy who came over here and spilled his guts and gave everything he had wants: for our country to love us as much as we love it.” The moral was plain, Darda argues: “Veteran status has less to do for Rambo with wearing the uniform than with waving the flag.”

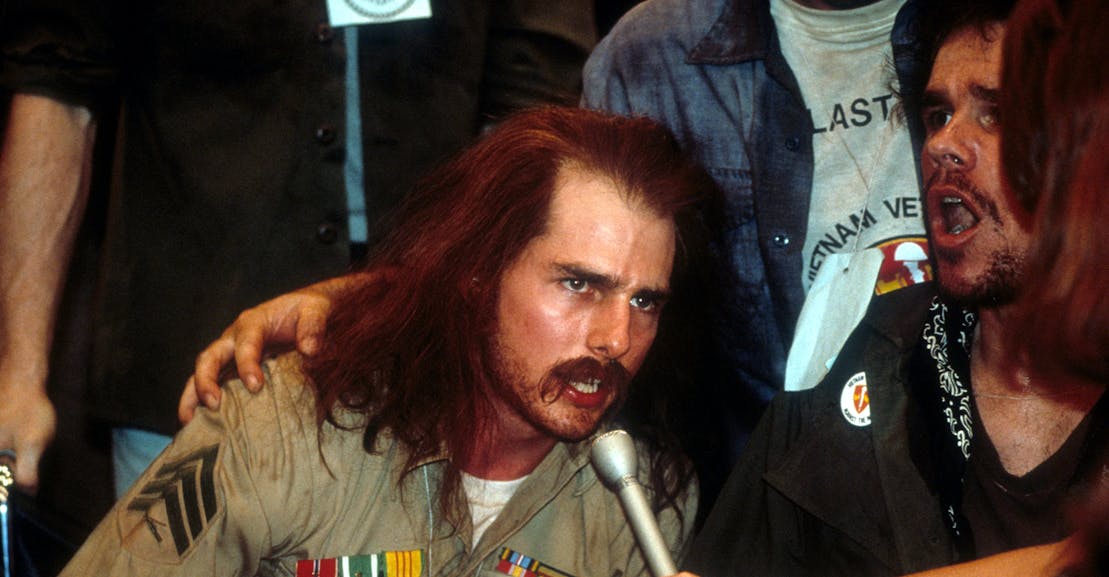

In the world of literature, meanwhile, a new cohort of Vietnam authors, all white and male, such as Tim O’Brien, Larry Heinemann, and Robert Olin Butler, gained canonical stature in American letters—Heinemann’s Vietnam vet novel, Paco’s Story (a “liberal answer to the Rambo films,” Darda writes) famously beat out Toni Morrison’s Beloved for the 1987 National Book Award. The same white male–dominated narrative template held for Vietnam memoirs, such as Ron Kovic’s Born on the Fourth of July, which inspired both Springsteen’s anthem and a big-screen adaptation by Oliver Stone.