Slate has relationships with various online retailers. If you buy something through our links, Slate may earn an affiliate commission. We update links when possible, but note that deals can expire and all prices are subject to change. All prices were up to date at the time of publication.

The members of OutKast position themselves between two parallel renderings of democracy: the irony of Southern Black folks’ upholding the purity of democracy as an idealistic access to better life and the counternarrative of democracy in the South as a threat to their very existence. OutKast’s recognition of not only their marginalization but also their refusal to acknowledge that the South does move on after 1968 is significant in using their musical catalog as a blueprint for updating why the hip-hop South is introspective and reflective of how young Blacks exist at the sharp intersections of expected performance, idealistic longing, and jarring realities of the contemporary American South.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

This reckoning is amplified at the 1995 Source Awards, where OutKast pushes past the geographic and cultural boundaries of the region or “Southness” into the experimental and meta-cultural possibilities of Southern Black expression. The Source Awards’ dominantly New York audience, in addition to their booing, jolts the ear and affirms hip-hop’s hyper-regional focus in the early to mid-1990s. The booing crowd identifies hip-hop as Northeastern, urban, and rigidly masculine, an aesthetic that was a daunting task for non-Northeastern performers to try to break through. Even celebrated West Coast artists like Snoop Dogg, who menacingly and repeatedly asked the crowd “You don’t love us?” during the show, indicated the challenge of being recognized—and respected— by Northeast hip-hop enthusiasts. That night in 1995 proved to be the climax of the conflict instigated by both West Coast Death Row Records and East Coast Bad Boy Records, the bitter lyrical and personal battle between Tupac Shakur and Notorious B.I.G., and OutKast, a Southern act, chosen as “Best New Rap Group.” The crowd’s increasingly despondent sonic rejection of hip-hop outside of New York foregrounds the premise for reading OutKast’s acceptance speech as blatant and unforgiving Southern Black protest, a rallying cry for forcefully creating space for the hip-hop South to come into existence.

Advertisement

Christopher “Kid” Reid and Salt-N-Pepa presented OutKast their award. Upbeat and playful, Kid said, “Ladies help me out,” to announce the winner, but there is a distinctive drop in their enthusiasm when they name OutKast the winner of the category. The inflection in their voices signifies shock and even disappointment, as Kid quickly tries to be diplomatic by shouting out OutKast’s frequent collaborators and label mates Goodie Mob. The negative reaction from the crowd was immediate, sharp, and continuous booing.

Big Boi starts his acceptance speech, dropping a few colloquial words immediately recognizable as proper hip-hop—“word” and “what’s up?” Over a growingly irritated crowd, Big Boi acknowledges being in New York, “y’all’s city,” and tries to show respect to the New York rappers by crediting them as “original emcees.” Big Boi recognizes he is an outsider, his Southern drawl long and clear in his pronunciation of “South” as “Souf,” yet he attempts to be diplomatic and respectful of New York. There is also a recognition that where he is from, Atlanta, is also a city: His term, “y’all’s city,” is not only a recognition of his being an outsider but a proclamation that he, too, comes from a city—except it is a different city. Big Boi’s embrace of Atlanta as urban challenges previous cultural narratives of Southerners as incapable of maneuvering within an urban setting. Because of a long-standing and comfortable assumption that the American South was incapable of anything urban—such as mass transit, tall buildings, bustling neighborhoods, and other interchangeable forms of communities—beliefs about Southerners’ perspectives remained aligned with rural, read as is, “country” and “backward,” sensibilities incapable of functioning in an urban cultural setting. These sensibilities often played out in longhand form via literature or in popular Black music, with a focus on dialect and language standing in as a signifier of regional and cultural distinction.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Consider Rudolph Fisher’s Southern protagonist, King Solomon Gillis, from the 1925 short story “City of Refuge.” Fisher characterizes Gillis, a Black man from rural North Carolina, as naïve and awestruck not only about New York but about city life in general. As the story opens, Fisher describes Gillis’ ride on the subway as “terrifying,” with “strange and terrible sounds.” References to the bang and clank of the subway doors and the close proximity of each train as “distant thunder” are particularly striking, a subtle sonic nod to Gillis’ rural Southernness and his inability to articulate the subway system outside of his limited Southern experiences. The references to “heat,” “oppression,” and “suffocation” also suggest Southern weather as well as a belief about the American South as an unending repetition of slavery and its effects.

Advertisement

Advertisement

It is important to point out that Gillis certainly is not a fearful man in the literal sense: He migrated to Harlem out of necessity and desperation, in fear of being lynched after shooting a white man back home. Yet Fisher’s attention to sound positions Gillis as an outsider. Further, Fisher describes Gillis as “Jonah emerging from the whale,” a biblical allusion to triumph over a difficult situation and a reference to rebirth, the possibility of a new life and new purpose. This can be associated with the biblical reckoning of Southern Black folks migrating out of the South to seek socioeconomic change and advancement. Still, the transition of Southern Black folks to life in the city is not easy: Gillis’ train ride symbolizes the move from one difficult landscape to another. Although Gillis is ultimately confronted with the brutality he was trying to avoid in North Carolina, his repeated proclamation, “They even got cullud policemans!” amplifies his Southernness and naïveté. Fisher’s intentional use of written-out dialect and the repetitiveness of Gillis’ awe of seeing Black police officers blot out the characteristic of region but not white supremacy. Gillis’ acceptance of Black police officers blurs the binaries of the Great Migration as a testament to Black folks looking for socioeconomic change outside of the American South, a terror-ridden space for Blacks. It also suggests, however, the unfortunate anxiety of those who decide to remain in the South, complacent in the lack of social equality.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Seventy years later, Big Boi, as a Georgian, returns to New York with the confidence of both rural and Southern sensibilities outside of the immediately recognizable urban trope that is embodied in New York. Big Boi’s full embrace of being “cullud,” in both the linguistic and cultural elements that Fisher’s longhand dialect represented as authentic Southernness, is jarring, because his intentional embrace of Southern Blackness as othered anchors his approach to rap music. Big Boi does not posture the South as a space or place in need of escape or reposturing. Rather, the hyperawareness from both Big Boi and André 3000 in front of the predominantly New York crowd ruptures the accepted narrative of the South as needing saving by non-Southern counterparts. Big Boi’s speech forces the audience to deromanticize its notions of Northeastern supremacy and recognize the South as capable of hip-hop. Their direct booing is a sonic representation of that discomfort. From this perspective, André’s now iconic remarks in their acceptance speech further emphasized Big Boi’s departure from reckoning with Northeastern hip-hop as the standard. He stumbles in his speech, possibly because of nerves or irritation, and, like Big Boi, must talk over the crowd. André talks about having the “demo tape and don’t nobody wanna hear it,” a double signifier of being rejected for his Southernness and the difficulty of breaking into the music industry. André’s frustration with being unheard as a Southerner can also be extended into the actual production of the tape by OutKast’s production team Organized Noize, who drew from Southern musical influences like funk, blues, and gospel to ground their beats. André’s call to arms, “The South got something to say,” rallied other Southern rappers to self-validate their music. It is important to note that André’s rally called to the entire South, not just Atlanta. This is significant in thinking about Southern experiences as nonmonolithic, the aural-cultural possibilities of multiple Souths and their various intersections using hip-hop aesthetics.OutKast moves past their rejection at the Source Awards via their second album ATLiens (Atlanta aliens), which offered an equal rejection of hip-hop culture’s binaries. The album’s use of otherworldly sonic signifiers, such as synthesizers and pockets of silence that sound like space travel, embodied their deliberate isolation from mainstream hip-hop culture and the beginnings of Stankonia, or the hip-hop South.

Advertisement

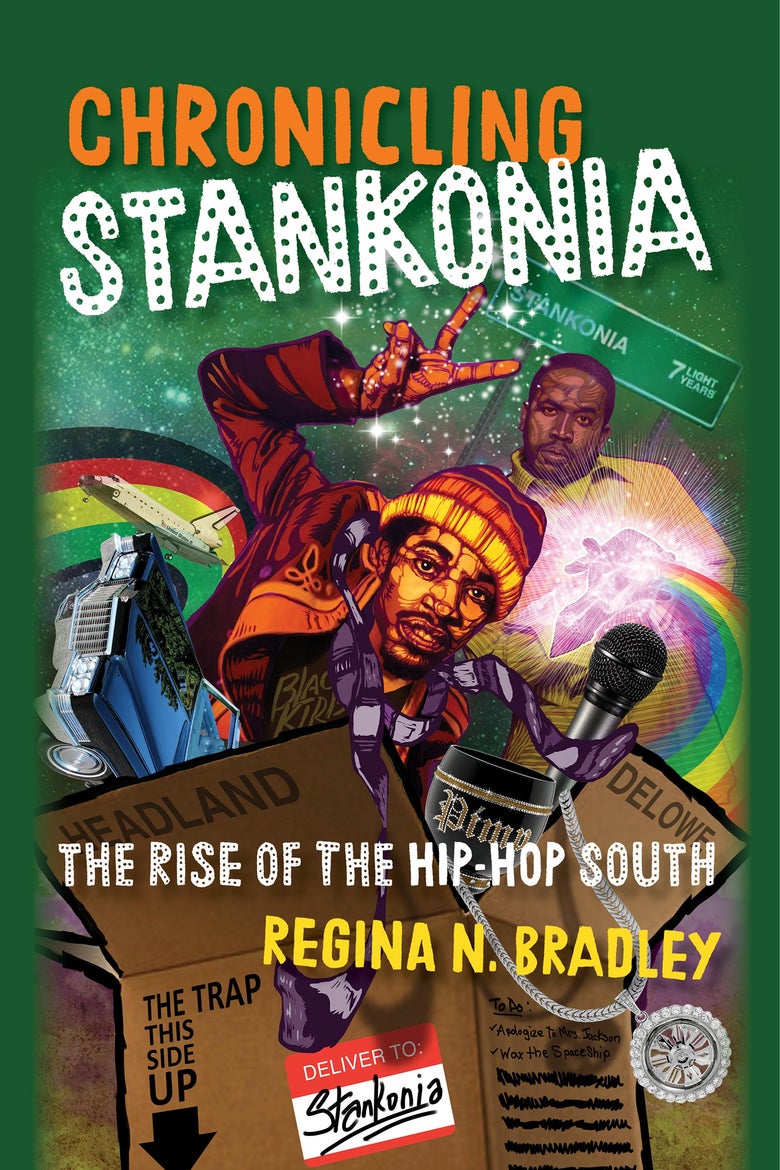

From CHRONICLING STANKONIA: THE RISE OF THE HIP-HOP SOUTH by Regina N. Bradley. Copyright © 2021 by Regina N. Bradley. Used by permission of the University of North Carolina Press.

<section data-uri="slate.com/_components/product/instances/cklbalpti00103e6bo90eps2e@published" class="product " data-product-name="Chronicling Stankonia: The Rise of the Hip-Hop South” data-product-price=”$19.95″ readability=”0.47368421052632″>

By Regina N. Bradley. The University of North Carolina Press.

For more on this, listen to this episode of Hit Parade, Slate’s podcast about the history of the Billboard charts: