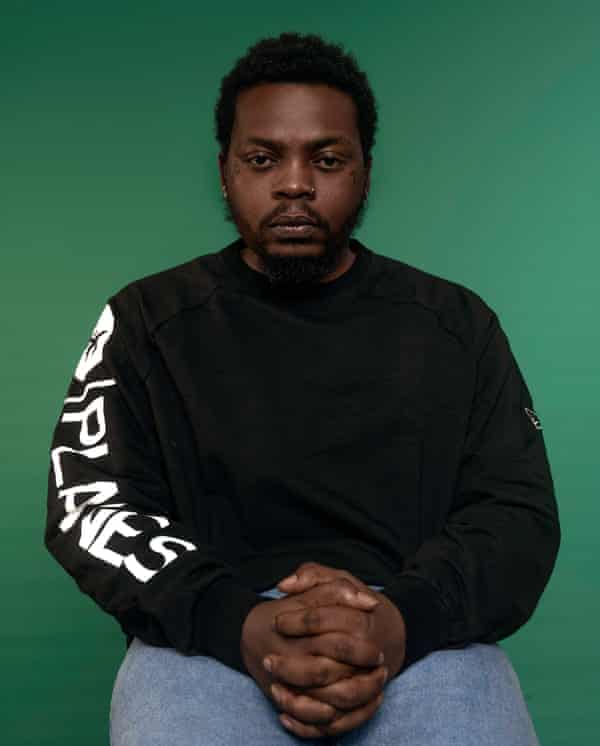

Bariga, a sprawling northern suburb of Lagos, Nigeria that is home to more than 700,000 people, is infamous for its impoverished housing and gang culture – and for pushing a raw, jarring sound into the Nigerian mainstream. Olamide, long one of Africa’s biggest music stars, was one of the kids responsible for that shift: 13 years ago, he was walking the streets of Bariga, plotting his way out.

“Surviving was hard,” says Olamide, now sitting in a comfortable Lagos home on a sunny Friday afternoon. “Bariga was not far from the other slums you see across the world, from Mumbai to New York and London – life in the ghetto is almost always the same everywhere. There were days when being able to afford three square meals was a big deal for my family. All of that motivated me to hustle hard – I wanted to see the whole world and experience different cultures from what I grew up seeing.”

Olamide Adedeji grew up listening to Yoruba music legends such as King Wasiu Ayinde Marshal and King Sunny Adé, but it was the contrast of DMX’s growling bars and Jay-Z’s ice-cool lyrics that appealed to him when he started making his own music. He is now advertised on the side of London buses and has scored millions of global streams, with a versatile artistry that spans delicate Afropop and harder dance tracks as Yoruba lyrics bleed into English and back again.

His first hit single, Eni Duro, recorded mostly in Yoruba, was released in 2010. Faced with juggling his music career and a university education outside Lagos, he left the latter in his third year, and his single arrived just as Nigerian music was undergoing a subtle rewriting of its pop conventions. Songs recorded in native languages had been relegated to the fringes of the industry, but a class of rappers from mainland Lagos – away from the city’s wealthy islands and peninsulas – then surged to popularity with incisive music that wove tales of street realities into boisterous hits. The positive acceptance of Eni Duro instantly made Olamide one of the wave’s most identifiable faces.

“Doing indigenous rap came with a lot of responsibilities because we had to come correct,” he says. “I knew I couldn’t do this alone: I was doing a lot of collaborations. A-list, B-list, whatever – I kept collaborating with everyone as long as I felt they were pushing and making good music.”

One year after Eni Duro, he released his debut album Rapsodi to critical acclaim. In 2012, his second album YBNL set off an unparalleled run of productivity: while peers such as Wizkid and Davido drip-fed singles, Olamide orchestrated a series of grand album projects, releasing an album a year until Lagos Nawa in 2017. “At the beginning, I was just making music as a kid: I sang based on how I was feeling at that moment,” he says. By the middle of the 2010s, his music had taken a slicker, yet urgent format suited to clubs: “I told myself I was done with rap music and just targeted making club bangers.”

Tracks such as Bobo, Lagos Boys and Wo!! showed his evolution from upstart rapper to pivotal pop figure . But despite that keen business sense – and even as Afrobeats became a global phenomenon in the mid-to-late 2010s – he never lobbied for foreign collaborations that could break him in international markets. “I’m never going to be desperate, or make funny moves because I’m trying to be successful,” he explains. “I’m an authentic person and that’s what my brand stands for.”

But in 2020, Olamide tiptoed on to a wider stage by cutting a deal with US label and distributor Empire. “Olamide’s history is deeply rooted in Nigeria,” says the company’s chief operating officer Nima Etminan, who visited him in Nigeria with founder Ghazi Shami to win him over. “I’ve witnessed the love and respect he receives not just as a musician, but as an inspirational role model for the youth. Despite a deep catalogue, he’s still just scratching the surface of his true potential as a global artist.”

The deal, which allows Olamide to release music on his own label while Empire handles global distribution, has renewed his prolific streak. Last year, he released Carpe Diem, a gorgeous body of work packed with balmy melodies and lyrics about overcoming low points. He’s just released his ninth album, UY Scuti. It is another evolution, finding Olamide cooing suggestively about love. “My priority is to express myself freely like a bird right now,” he says. “If I feel something, I just want to go in there and talk about it as much as I can. It’s back to how it all started for me: just making music with my feelings and however it comes.”

Olamide still tries to stay in touch with people he has known since Bariga. “I go on Facebook and message them, but most times they think it’s a fake account. They just don’t believe it’s me and tell me not to text them again,” he says, suppressing a grin. There is a slight change in his countenance when I ask if he has survivor’s guilt from making it out of the ghetto. “Unfortunately, there’s only so much I can do,” he says, and adds that he is planning charitable programmes for people from these disadvantaged communities in 2022.

On Triumphant, a song from Carpe Diem, Olamide rapped about “changing the narrative for the ghetto youth”, a topic that still means a lot to him. “That was essential for me,” he says of that lyric. “Many people have a very limited understanding of the ghetto. They think it’s all ruggedness and violence. The ghetto is way beyond that. Being from the ghetto is not only about guns and knives or living dangerously, it’s about being smart with your choices and moves.

“If you’re smart enough you can do better for yourself. I don’t want people in the ghetto to feel like they are inferior or in competition with anybody. The important thing is looking out for yourself and trusting your process.”