This post was originally published in FIN, the best newsletter about fintech; subscribe here.

A debate that’s been bouncing around for years is whether fintech’s innovation can truly help minority and underbanked consumers, or whether fintech is largely a 21st-century costume for financial predators that have been around for decades. (This post deals primarily with the US experience, but it’s a global question, especially in Latin America and Africa).

One critical issue is access: given that the underbanked typically have lower access to broadband and mobile phones than the rest of the population, it’s not obvious that cutting-edge tech solutions would reach them more effectively than traditional banks and legacy money transfer services (like Western Union and MoneyGram). And, as has been covered voluminously, banking services for Black Americans have been disgraceful at best; it’s little surprise that nearly half of Black households remain un- or underbanked.

But the evidence is now overwhelming that fintech is reaching the underbanked and other populations marginalized by traditional banking.

The best measure of this is the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation’s (FDIC) Household Use of Banking and Financial Services survey. The survey is conducted every other year, so unfortunately the most recent data, from 2019, is pre-COVID (the 2021 survey results should be released in a few weeks). But even then, the FDIC found that among households in general, P2P payment systems—such as PayPal and Zelle—were far more popular than other nonbank financial transactions—such as money orders and check-cashing services. A full 31.1% of households reported using such P2P apps; the next highest product usage, as old-fashioned as it sounds, was money orders, at 11.9%.

As one might predict, the higher a household’s income, the more likely it is to have used a P2P payment service. Nonetheless, these services showed remarkable adoption in communities that traditional banks have had difficulty reaching (to put it charitably). For example, 20.2% of Hispanic households reported using international remittance services, such as Western Union, while 24.3% reported using P2P payments. The FDIC also found that 27.7% of Black households and 38% of Asian households had used a P2P payment system.

Again, this was all pre-COVID. This week, the Pew Research Center released its own survey on payment apps, based on questions asked in July, with startling results. While Pew didn’t ask an overall question about payment app use, it found that an astounding 57% of all US adults say they have used PayPal at least once. Among Americans between ages 30 and 49, 66% have used PayPal. Even 48% of lower income Americans have used PayPal.

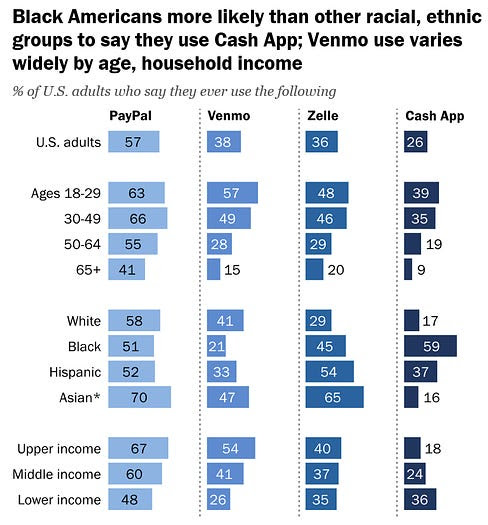

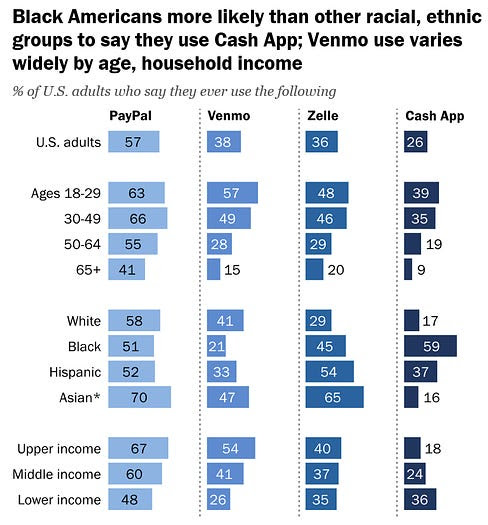

What’s especially striking about the Pew survey is that not only have payment apps successfully penetrated American minority communities, but there is significant variation in which groups use which apps. This chart is illuminating:

|

One figure that really stands out is that 59% of Black American adults say they have used Cash App (which is part of Square/Block), more than three times the percentage of white Americans who’ve done so. Part of this reflects the tremendous growth that Cash App experienced during the pandemic. People who’ve followed Square/Block for years may not have gotten used to just how thoroughly Cash App now dominates the company’s business. Starting in the second quarter of 2020—that is, when COVID became a global epidemic and lockdowns made contactless payments more desirable—Cash App revenue began to surpass the revenue from Square’s traditional sellers. The growth has slowed somewhat, but the company still predicts that in 2023 Cash App will bring in about $12 billion in revenue, which is about 2/3 of the total revenue that Block had in all of 2021.

But the relationship between Cash App and Black Americans goes deeper and longer than lockdowns. Back in August 2019, Peter Rudegeair wrote in the Wall Street Journal about the surprising ubiquity of Cash App mentions in rap music (see Iggy Azalea in “Kreme”: “Hit me on my Cash App, check it in the morning.”)

Rapper Travis Scott once gave away Cash App gifts to fans who quoted his lyrics on Twitter. In the Journal article, Square cofounder Jack Dorsey said he wasn’t aware of how the Cash App meme took off in hiphop, although it’s hard to believe that Square’s relationship with Jay-Z and TIDAL isn’t a factor. It’s less clear why Asian and Hispanic Americans are so much likelier than average to use Zelle.

Getting un- or underbanked communities to use fintech apps is, however, only one part of the equation. One revealing area that Pew explored is the possibility of getting scammed through these services; by now the stories of fraud on Zelle are legendary. For those who don’t use these apps, particularly older Americans, trust is a major reason why. Even among those who do use the services, a third say they have little or no confidence in the ability of the services to keep their money and data safe (presumably this is an acceptable tradeoff for convenience). Moreover, Black and Hispanic app users report being hacked or scammed more often than average.

Of course, the real fear about the underbanked is less that they will scammed by outsiders than that the financial services themselves—such as paycheck cashing companies, at least until recent crackdowns—are legal scams. The good news is that the basic services offered by Venmo, Zelle and Cash App are free of charge, reasonably regulated and hugely beneficial for consumers. As these companies strive to become “superapps,” tacking on loans, crypto and Buy Now Pay Later services, the risk of being ripped off increases, but for the larger public companies, it’s reasonable to expect regulators to stay on top of this. Whether the ability to make easy, P2P payments via a cell phone will actually change the economic status of underbanked communities remains to be seen. But the bigger question is why so little is written about the tremendous success that fintech companies have had reaching tens of millions of Americans whom banking has excluded for decades.