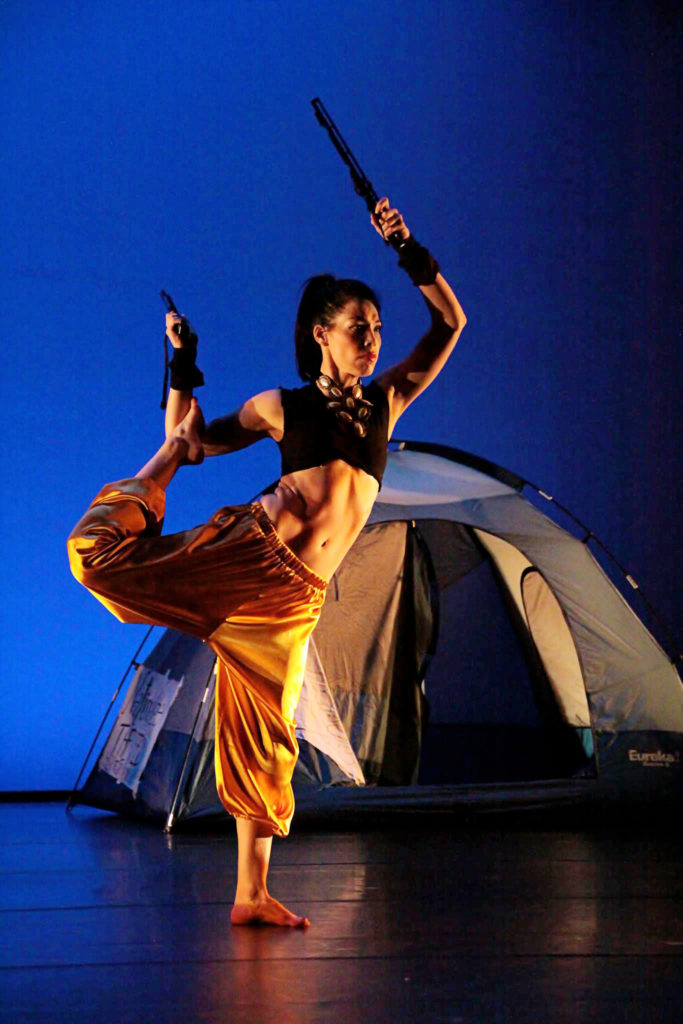

On occupied Tewa lands in downtown Albuquerque, New Mexico, the Foundations of Freedom crew—decked out in streetwear and sneakers—takes the floor at Breakin’ Hearts, an annual hip-hop event. Emcee Randy L Barton enlivens the room with an EDM mix of Indigenous vocals and drumming. Encircled by a crowd of about 250 people, the Indigenous dancers in the cypher activate a tribal energy; arms undulating, torsos rolling, knees carving, footwork weaving, shaping and reshaping. Their performance is a seamless intermingling of hip hop and Indigenous culture.

Native American dance is often believed to be a purely “traditional” style, and while tradition is reflected and preserved in the dances, the form is so much more than that. For generations, dance has been a central mode of emotional expression, leading to a diverse array of dances rooted in the heritage and cultures of the many Indigenous tribes of North America. There are religious and ceremonial dances not open to the public, traditional dances, and social dances such as many powwow dances. Dancers’ responding to their environments is inevitable, as is young dancers’ interest in mixing in contemporary ideas that reflect their current experiences. In the past few decades, this has given rise to the growth of a new fused style: Native American hip hop.

This innovation has produced a style of steps and movements that are not discernably different from hip hop. There is, however, a distinct flavor which is created by hip-hop music fused with Indigenous song and by movements that expand the distinct urbanism of hip hop’s repertoire with an expressive embodied reference or reverence to nature. It’s a contemporary storytelling of the Indigenous experience in the U.S. that bridges rural and urban, oppressed and empowered, individual and collective.

Native American dance and hip hop began weaving into a unique urban and contemporary form in the late 1990s. Yet dancer Anne Pesata, who is Jicarilla Apache, notes that there were already internationally recognized Indigenous hip-hop dancers, such as b-boy Ariston Ripoyla (aka “Remind”), who were building their careers even earlier. In an interview with the multicultural platform Rep Ur Tribe, Remind describes himself as being activated through hip hop to recognize his Native roots and remember his culture: “Breaking is not so far out from what tribes were doing already,” he says.

“Both communities share a similar socioeconomic experience, so both communities relate to one another.”

Anne Pesata

Pesata describes the fusion in similar terms. “In neither powwow nor freestyle are steps taught,” she says. In the context of competition, both styles encourage dancers to showcase their best moves and signature phrases to illustrate what they can do, rather than relying on the lens through which Eurocentric forms understand dance steps. Pesata regards movement as existing in a fluid state rather than the solid state of permanence that conceptualizing “steps” creates.

Throughout the 2000s and 2010s, Nakotah LaRance, a champion hoop dancer who toured with Cirque du Soleil, became known for incorporating modern elements, such as hip hop and moonwalking, into his hoop dances. Often dancing in modern casual clothing to EDM/Indigenous-fused music, LaRance switched seamlessly between traditional and contemporary hoop-dance performances.

More recently, Native American hip hop was brought into the spotlight by the crew Indigenous Enterprise when it appeared on Season 4 of “World of Dance” in 2020. Although founder Kenneth Shirley clarifies that it’s not a typical style for the troupe, “For ‘World of Dance,’ we included a section to draw in the audience and the judges with music and dance they would relate to.” (Although he felt the approach was effective, the crew was nonetheless eliminated in the qualifiers round.)

Yet fusing other styles into the movement isn’t something that’s out of the ordinary for Indigenous dancers: Shirley notes that hip hop is not absent from his traditional dance. “I have integrated hip-hop or ballet steps that have inspired me into my fancy dance,” he says, of the popular powwow dance. “Adding contemporary movements is part of natural evolution of the tradition.”

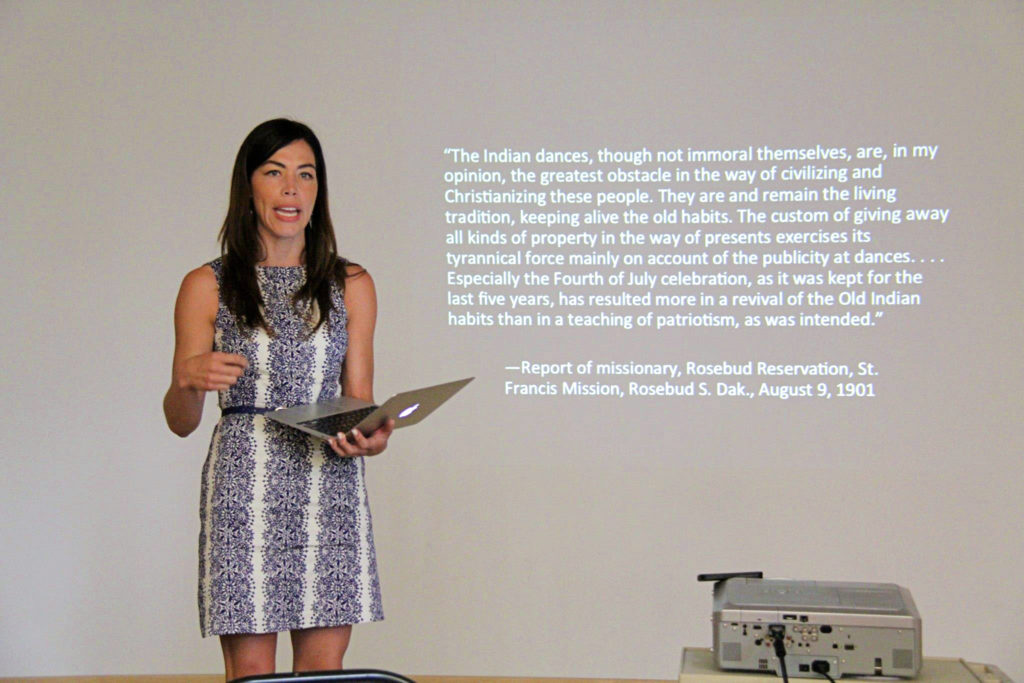

Those unfamiliar with this practice, however, often view fusion as a form of inauthenticity, which has become a challenge to widespread acceptance. “Mainstream narratives tend to relegate Native peoples and practices to the past and view them as ‘inauthentic’ when they incorporate aspects of modernity,” says UCLA assistant professor of dance studies Dr. Tria Blu Wakpa. In contrast, Blu Wakpa says the fusion can more realistically be understood as “an extension of Indigenous practices.”

From the perspective of the hip-hop community, Indigenous dance fits right in. “Long ago, hip hop’s architects envisioned a creative community where anyone’s heritage, culture and identity could be grafted onto a core set of artforms and principles: deejaying, emceeing, breaking, graffiti and knowledge,” says Ben Ortiz, assistant curator of the Cornell Hip Hop Collection, which collects and archives historical artifacts of hip-hop culture at Cornell University. “Traditional powwow dancing collaged with popping or breaking is not only dope, it feels completely natural and at home in the hip-hop community.”

Pesata describes the crossover being possible because “both communities share a similar socioeconomic experience, so both communities relate to one another.” The diverse people of color who make up the hip-hop community and the Indigenous communities have both dealt with appropriation and being tokenized, oppressed and marginalized. And both have remarkable parallels in cultural practices: Drumming parallels the deejay, chanting the emcee, and petroglyphs the graffiti art. Pesata points out that the concept of “battle” is core in both styles. Historically, there are war dances in Indigenous tradition and today, there’s high-stakes competition powwow dancing. In both hip hop and Native dancing, the competition inherent in battles has pushed innovation, driving the forms’ evolutions.

Blu Wakpa sees Native American hip hop as part of Indigenous futurism: “The weaving of hip hop and Native dance can be viewed as an innovation, an indigenizing of hip hop that provides generative possibilities for Native creativity, expression, healing, joy, resistance and connection.” By evolving tradition to reflect the world these artists live in today, they’re becoming more visible as part of contemporary society, changing the narratives fueled by the reservation system while also reconnecting with pride to their own history.