(Picture credit score: Edward Burtynsky, Nicholas Metivier Gallery, Toronto / Flowers Gallery, London)

Canadian photographer Edward Burtynsky discusses his startling and unexpectedly chic images – ‘an prolonged lament for the lack of nature’ – with Gaia Vince.

F

For greater than 40 years, the Canadian photographer Edward Burtynsky has recorded the influence of people on the Earth in large-scale photographs that usually resemble summary work. The author Gaia Vince, whose guide Nomad Century was revealed in 2022, interviewed Burtynsky for BBC Tradition about his newest undertaking, African Research.

African Research is now collected in a guide and is on show at Flowers Gallery, Hong Kong till 20 Might 2023.

Gaia Vince: Together with your footage we see the outcomes of our consumption habits or our existence, in our cities. We see the outcomes of that far, far-off in a pure panorama made unnatural by our actions. Are you able to inform me about African Research?

Edward Burtynsky: I used to be studying that China was starting to offshore to Africa, and I assumed that will be actually attention-grabbing to observe. General it has been a decade-long undertaking, researching after which photographing in 10 nations. I began in Kenya, after which Ethiopia, then Nigeria, after which I went to South Africa.

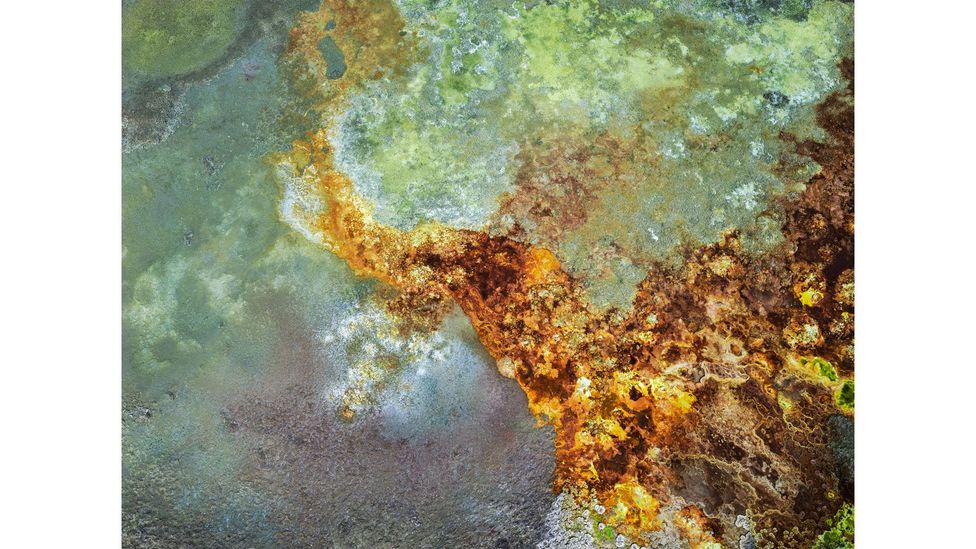

Sulfur Springs #1, Danakil Despair, Ethiopia, 2018 (Credit score: Edward Burtynsky, Nicholas Metivier Gallery, Toronto / Flowers Gallery, London)

GV: I observed that you simply went to the Danakil Despair in Ethiopia – inform me about that.

EB: All our drone tools wasn’t working as a result of we have been 400 ft under sea degree. So the drone GPS was saying: ‘You are not imagined to be right here. You are on the backside of the ocean’. We needed to flip off our GPS as a result of we could not get it to calibrate, it did not know the place it was.

The Danakil Despair is an enormous space masking about 200km by 50km. It is generally known as one of many hottest locations on the planet and has been known as ‘hell on Earth’. I’ve by no means labored in temperatures over 50C. At night time, it was 40C – even 40 is sort of insufferable. And we have been sleeping outdoors as a result of there aren’t any buildings, there aren’t any inside areas. We spent three days there capturing; within the mornings we’d stand up after which drive so far as 25km to get to our places. One such location was Dallol, a volcanic hellscape of sulfurous springs. Attending to it required that we supply all our heavy tools whereas climbing jagged rocks for about 1.5km.

Camel Caravan #1, Danakil Despair, Ethiopia, 2018 (Credit score: Edward Burtsynky, Nicholas Metivier Gallery, Toronto / Flowers Gallery, London)

GV: It is bodily extraordinarily demanding what you are doing.

EB: That was! Yeah, it’s usually and also you’re working with each the late night gentle and the early morning gentle. So that you’re working each ends of the day and you actually do not get a whole lot of relaxation in between that as a result of to get to the placement within the morning with that early gentle, you must be up often an hour and a half earlier than that occurs. However you do no matter it is advisable do. After I’m in that house, I am identical to, ‘here is the issue, here is what I wish to do, what’s it going to take?’

Sulfur Springs #2, Danakil Despair, Ethiopia, 2018 (Credit score: Edward Burtynsky, Nicholas Metivier Gallery, Toronto / Flowers Gallery, London)

GV: Africa is the final huge continent that has giant quantities of wilderness left. Partly due to colonialism and different extractive industries from the World North, the economic revolution in Africa is occurring now. So there’s this juxtaposition between that wild panorama and these very artificial landscapes that people have created – how do you perceive that your self?

EB: The African continent has a whole lot of wilderness left and there are a whole lot of sources, like the invention of oil in Tanzania and northern Kenya and different locations. There is a huge rush for oil pipelines to be moving into there. Notably with China’s involvement, there are a whole lot of performs to construct infrastructure in alternate for entry to sources, whether or not it is farmland for meals safety, whether or not it is oil, yellowcake uranium, and so forth.

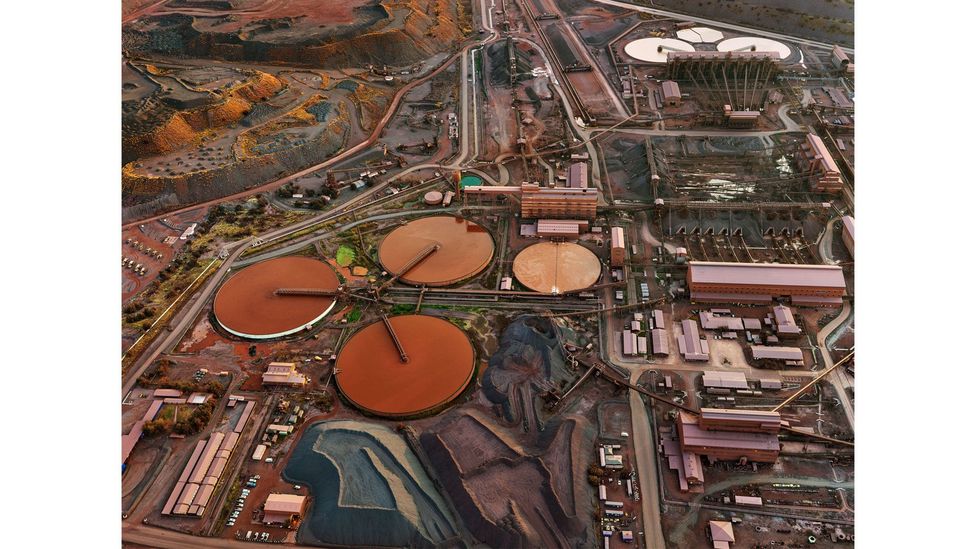

Uranium Tailings #13, Husab Uranium Mine, Namibia (Credit score: Edward Burtynsky, Nicholas Metivier Gallery, Toronto / Flowers Gallery, London)

It is like financial colonialism. I do not suppose they need full management of those nations. They need an financial benefit, they need the sources and so they need the chance these sources present. For instance, the Chinese language personal the biggest deposit of uranium yellowcake in all the African continent – I photographed that mine.

GV: I additionally noticed your unbelievable pictures from the shoe manufacturing unit in Ethiopia. It appears fully transposed from China to Africa.

Huajian Shoe Manufacturing unit #1, Dukem, Ethiopia, 2018 (Credit score: Edward Burtynsky, Nicholas Metivier Gallery, Toronto / Flowers Gallery, London)

EB: A few of the images have been taken in Hawassa, which is a 200-acre Particular Financial Zone, like Shenzhen in China. The Chinese language constructed what they name sheds, that are extra like warehouses. They constructed 54 of those sheds, with the roadway. So you may have a look at that image – with the roadways, with the lighting, with the plumbing, with every little thing. All achieved, begin to end, 54 of those have been constructed inside one 12 months – all of the constructions have been introduced by ship after which by rails into Ethiopia and erected like a Meccano set. And once I was there, they have been filling these sheds with stitching machines and textile makers.

Hawassa Industrial Park #1, Awassa, Ethiopia, 2018 (Credit score: Edward Burtynsky, Nicholas Metivier Gallery, Toronto / Flowers Gallery, London)

GV: The commercial revolution began in England and the factories of the North, and nonetheless if we dig down, it is simply fully polluted soils and landscapes, after which that was offshored to poorer nations and so forth… That cycle is hitting Africa. However the place is it going to be offshored subsequent? We will not simply hold offshoring. There is not one other place.

EB: I usually say that ‘that is the tip of the highway’. We’re assembly the tip of globalisation and the place you may go. And it has to depart China as a result of they’re gagging on the air pollution. Their water’s been fully polluted. The labour drive has stated: ‘I am not going to work for reasonable wages like this anymore.’

So as an alternative the Chinese language are coaching textile staff – primarily feminine – in Ethiopia, and Senegal, and inside two or three months, these women are behind stitching machines and on par with Chinese language manufacturing charges and what they might’ve anticipated out of a Chinese language manufacturing unit. That is their objective. And so they’re coaching these younger 16, 17-year-olds, taking them away from their households after which placing them proper into the stitching machine sweatshop.

C&H Clothes #3, Diamniadio Industrial Metropolis, Senegal, 2019 (Credit score: Edward Burtynsky, Nicholas Metivier Gallery, Toronto / Flowers Gallery, London)

GV: On the coronary heart of your photographs, they’re very political, aren’t they?

EB: Nicely, I have been following globalism however I began with the entire thought of simply taking a look at nature. That is the class the place I started, the thought of ‘who’s paying the value for our inhabitants progress and our success as a species?’ Broadly talking, it is nature. It is the animals, the bushes, the prairies, the wetlands, the oceans – that is the place the value is being paid, you understand, and so they’re all being pushed again. These are all of the pure environments on the planet that we used to coexist with, that we’re now completely overwhelming in a manner. So nature’s on the core – and all my work is absolutely form of an prolonged lament for the lack of nature.

N4 Street #1, Nguekhokhe, Senegal, 2019 (Credit score: Edward Burtynsky, Nicholas Metivier Gallery, Toronto / Flowers Gallery, London)

GV: Do you see your self as holding up a mirror to the world because it adjustments, and because it turns into extra human-dominated? Or do you see your self as an activist – are you attempting to immediate change?

EB: Nicely, I would not say activist – any person as soon as talked about ‘artivist’ and I favored that higher. ‘Activist’ appears to lean extra into the direct political discourse – I do not wish to flip my work into an indictment, a two-dimensional form of blunt device to say, ‘that is improper, that is unhealthy, stop and desist’. I do not suppose it is that straightforward.

I feel all my work, in a manner, is displaying us at work in ‘enterprise as standard’ mode. I am attempting to point out us ‘these are all precise components of our world which can be unfolding each day so as to assist what’s now 8bn individuals, eager to have an increasing number of of what we within the West have’. I understood 40 years in the past, once I began wanting on the inhabitants progress, and I received an opportunity to see the dimensions of manufacturing, that that is solely going to get larger. Our cities are solely going to get extra huge.

I made a decision to proceed wanting on the human growth, the footprint, and the way we’re reaching world wide, pushing nature again to construct our factories, to construct our cities, to farm – we dwell on a finite planet.

Magadi Soda Firm #1, Lake Magadi, Kenya, 2017 (Credit score: Edward Burtynsky, Nicholas Metivier Gallery, Toronto / Flowers Gallery, London)

Going again to your unique query, I feel the time period ‘revelatory’ versus ‘accusatory’ has at all times been one thing that I am comfy with, in that I am pulling the curtain again and saying, ‘Look, guys, you understand, we are able to nonetheless flip this ship round if we’re good about it. However failing that, we’re playing. We’re betting the planet.’

GV: What do you suppose the chances are?

EB: The Canadian environmental scientist David Suzuki as soon as stated it rather well. He used the metaphor of Wile E. Coyote chasing the Street Runner – how hastily the Street Runner could make a pointy flip however Wile E. doesn’t change course, he retains going and runs himself proper over a canyon. Suzuki stated: ‘We’re at present over the air with our ft working. And the one query is, are we going to fall 10 ft or 500 ft?’

Salt Ponds #6, close to Tikat Banguel, Senegal, 2019 (Credit score: Edward Burtynsky, Nicholas Metivier Gallery, Toronto / Flowers Gallery, London)

GV: I feel one of many issues your footage present us is that we’re already falling. We do not see this destruction in our good air-conditioned workplaces within the US or in London. We do not essentially really feel the shock of that fall. However for people who find themselves residing on the sting, who’re residing within the Niger Delta, for instance, they’re already very a lot experiencing this fall.

Oil bunkering #2, Niger Delta, Nigeria, 2016 (Credit score: Edward Burtynsky, Nicholas Metivier Gallery, Toronto / Flowers Gallery, London)

And I feel that is one thing that your footage actually present. They convey a extra planetary perspective, however they carry it in a manner that we do not typically get to see. And one of many causes for that’s that they’re genuinely a special perspective. There’s a chook’s eye view there, an aerial shot, so we see one thing that we’d solely glimpse in a information reel or a picture in a journey guide. They convey it in, in a manner that you could by some means see that scale.

Salt Pans #32, Walvis Bay, Namibia, 2018 (Credit score: Edward Burtynsky, Nicholas Metivier Gallery, Toronto / Flowers Gallery, London)

EB: Images has the capability to try this, in case you perceive the way it works and the best way to use it. However we do not really usually see the world that manner, from above. When you have a look at a Peregrine falcon, they’ve the best decision of any retina of any animal on the planet, and scientists are unpacking it to know the best way to make sensors for cameras. In the same manner, pictures makes every little thing sharp and current . Seeing my work at scale, as huge prints, you may stroll as much as them and you may have a look at the tire tracks and you may see the small truck or particular person working within the nook.

Tailings Pond #4, Botswana Ash Firm, Sua Pan, Botswana, 2019 (Credit score: Edward Burtynsky, Nicholas Metivier Gallery, Toronto / Flowers Gallery, London)

GV: That’s the extraordinary energy of your footage – there may be this big scale. And at first, it is like an art work – it appears creative, summary, maybe a portray as a result of you may pick patterns. And then you definately begin to realise: ‘Truly no, that is one thing that is both pure or it is human made’. And then you definately realise these tiny little ants or these little markings are monumental stone-moving machines or skyscrapers or one thing actually huge. However you handle to deliver that absolute precision and element and focus into one thing that’s actually big. How do you do this?

EB: By and enormous I’ve used tremendous high-resolution digital cameras for the singular photographs. You can too lock drones up within the air, it will maintain the digicam even when it is windy up there; it’s going to continually be correcting for being buffeted. After which with that precision, with that capability to carry it there, I can use an extended lens and do a gaggle of photographs of that topic. I am controlling the high-resolution digicam by a video on the bottom – the digicam may very well be 1000 ft away – after which I can rigorously shoot all of the frames that I have to later sew collectively in Photoshop. Most of my work is single photographs on high-resolution cameras. The digicam I take advantage of now’s 150-megapixel.

Sishen Iron Ore Mine #3, Kathu, South Africa, 2018 (Credit score: Edward Burtynsky, Nicholas Metivier Gallery, Toronto / Flowers Gallery, London)

GV: Your footage are very painterly – do you see your self extra as an artist or extra as a photojournalist?

EB: I form of stroll that line. What I share with photojournalism is that there is a narrative behind it. There is a story behind it. I might say that I lead with the artwork however every little thing that I am photographing is linked to this concept of what we people are doing to rework the planet. So that is the overarching narrative, whether or not it is wastelands or waste dumps, mines or quarries.

Sand Dunes #1, Sossusvlei, Namib Desert, Namibia, 2018 (Credit score: Edward Burtynsky, Nicholas Metivier Gallery, Toronto / Flowers Gallery, London)

GV: You do additionally {photograph} some pure landscapes, there may be this sort of recurring sample that very often what you {photograph} nearly appears pure as a result of it has these pure patterns in it like repeating circles from agricultural monocultures or irrigation patterns or the extraction patterns in quarries and delta sludge, all of that, it additionally has these repeaters in nature that happen in crops and in pure river programs. I actually favored your landscapes from Namibia, these pure sandscapes with the traditional sculpting of the bone-dry panorama.

EB: I am main with artwork, so I am taking a look at artwork historic references, whether or not it is summary expressionism or different shared concepts with portray. I am going to have a look at a specific topic, then spend time on the best way to method it. What am I going to hyperlink it into in order that it seems in a manner that has a signature of the work that I have been doing over time, and in addition shares in artwork historical past? If summary expressionism by no means occurred as a motion, I do not suppose I might make these footage.

Desert Spirals #1, Verneukpan, Northern Cape, South Africa, 2018 (Credit score: Edward Burtynsky, Nicholas Metivier Gallery, Toronto / Flowers Gallery, London)

GV: It is nearly a translation, you are seeing these system adjustments and also you’re describing it to individuals of their language, in a well-known language that they already perceive from the tradition that they know – completely different creative actions.

EB: To me, it is attention-grabbing to say, ‘I’ll use pictures, however I’ll pull a web page out of that second in historical past’. And in case you have a look at it, all through my work I am pulling pages out of moments in historical past and saying, ‘Oh, that is the 18th-Century direct, fantastically composed method – a deadpan method to photographing – for example, the pyramids. I’ll use that, as a result of the shipbreaking yards in Bangladesh name for this method.’

Salt Ponds #4, close to Naglou Sam Sam, Senegal, 2019 (Credit score: Edward Burtynsky, Nicholas Metivier Gallery, Toronto / Flowers Gallery, London)

GV: I simply needed to speak to you in regards to the thought – one thing that you simply’re getting at together with your photographs – this concept that we live now on this human-changed world however however we’re in fact depending on the Earth for every little thing and we’re all interconnected. I’m wondering how far {a photograph} can go to explaining that extraordinarily sophisticated 3D idea of interconnectedness?

EB: One of many issues that pictures and documentary filmmaking can do is reveal these items repeatedly. It could actually present them, go to locations the place common individuals would usually not go, and haven’t any cause to go, like a giant open-pit mine. It could actually take you to the areas that we’re all depending on, oil fields and copper mines and cobalt mines. I feel it is extra compelling that manner. Individuals can soak up info higher than studying – photographs are actually helpful as a form of inflection level for a deeper dialog. I do not suppose they will present solutions, however they will actually lead us to consciousness, and the elevating of consciousness is the start of change.

With my pictures, I am coming in to look at, and my work has by no means been in regards to the particular person, it has been about our collective influence, how we collectively rearrange the planet, whether or not constructing cities or infrastructure or dams or mines.

African Research is now collected in a guide and is on show at Flowers Gallery, Hong Kong till 20 Might 2023.

If you want to touch upon this story or the rest you’ve got seen on BBC Tradition, head over to our Fb web page or message us on Twitter.

And in case you favored this story, join the weekly bbc.com options publication, referred to as The Important Checklist. A handpicked number of tales from BBC Future, Tradition, Worklife and Journey, delivered to your inbox each Friday.

;

Supply hyperlink