One unsettling sign of how big the business for posthumous hip-hop albums has become: DMX’s “Exodus,” which arrives just weeks after the gravel-voiced rapper’s death on April 9 at age 50, does so minus a planned appearance by the late Pop Smoke — because, DMX’s producer says, the verse in question ended up on one of Pop Smoke’s posthumous records first.

Released Thursday night, “Exodus” joins a tragic cavalcade of recent projects from hip-hop artists who died before their time, including 20-year-old Pop Smoke and 21-year-old Juice Wrld, both of whose 2020 LPs were among last year’s most commercially successful in any genre, as well as XXXTentacion (20), Mac Miller (26) and Lil Peep (21).

But DMX’s album also stands apart, not least because of his age — “Exodus” has a distinctly grown-up quality, with thoughts of nostalgia and fatherhood — and because he was part of a generation from before the era when digital recording enabled musicians to create vast stores of material that their survivors could later comb through.

Indeed, according to Swizz Beatz, who worked with DMX for years in the studio and oversaw the making of “Exodus,” this impressive 13-track set wasn’t intended to be a posthumous album at all. The producer says that he and DMX got to work on “Exodus” in the immediate wake of the rapper’s well-received July 2020 Verzuz battle with Snoop Dogg, which reinvigorated his career after some time in the wilderness; the idea was a kind of focused, high-level reintroduction of an artist whose fierce lyricism and unvarnished charisma led to a string of five No. 1 albums — including two in a single year — in the late ’90s and early ’00s.

DMX, who’d signed a new deal with the Def Jam label that helped turn him into a star, had the LP virtually finished when he died from a heart attack reportedly related to a drug overdose. (His death closely followed those of two other middle-aged rappers, MF Doom and Black Rob, and shortly preceded that of Digital Underground’s Shock G — an unhappy way to realize that hip-hop itself has been around for nearly half a century.)

Knowing his ambitions, it’s heartening to hear how much belief DMX had left in his signature approach: Though “Exodus” utilizes more cameos than he went for on his classic early records — among the splashier guests are Jay-Z, Lil Wayne, Nas, Snoop Dogg, Usher and U2’s Bono — the music still layers his gruff, chant-like vocals over hard-knocking beats smeared with vaguely gothic overtones; thematically, too, he puts across a familiar blend of threats, confessions and sexual advances — sometimes all in one song, as in “Take Control,” where Marvin Gaye’s sampled croon accompanies him as he imagines the resentments likely to grow out of an intimate bedroom encounter.

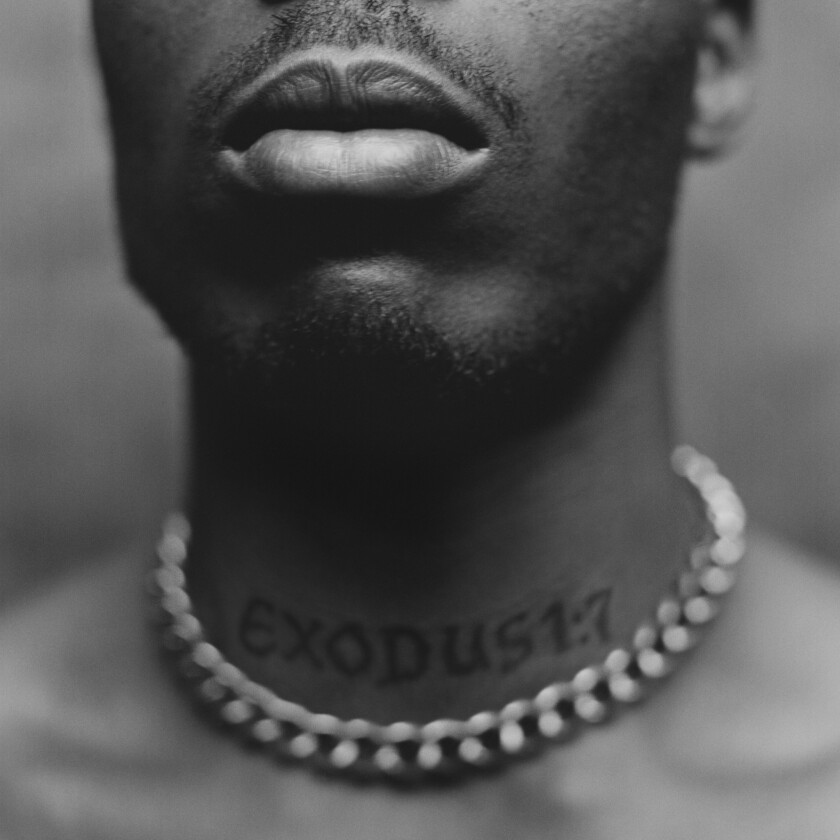

Cover of DMX’s 2020 album “Exodus”

(Def Jam Recordings)

“Hold Me Down,” with a reassuring hook sung by Swizz Beatz’s wife, Alicia Keys, ponders the durability of faith — “Devil working on me hard because God loves me,” DMX raps — while the swinging “Hood Blues” vividly flashes back to the Yonkers, N.Y. native’s rough upbringing. In “Money Money Money,” the track that was supposed to feature Pop Smoke (now replaced by Memphis rap star Moneybagg Yo), the men trade growling lines about danger and temptation; “Bath Salts,” which convenes a Big Apple dream team with former enemies Jay-Z and Nas, carries its menace more lightly: “I’m taking half, it’s just that simple,” DMX barks, clearly inspired by the friendly competition, “Or I can start popping n— like pimples.”

Ironically, perhaps, hearing DMX embrace his vintage sound makes you think about the influence younger rappers have taken from him even as they’ve left behind his straightforward boom-bap production for blearier styles. You could certainly hear him in Pop Smoke’s chesty rumble and in Juice Wrld’s songs about his precarious mental health; you can see him in the flashy yet tattered rock-star iconography favored by the likes of Trippie Redd and Playboi Carti.

In the tightness of its structure, though, the gratifyingly concise “Exodus” shares little with modern rap — particularly with bloated posthumous efforts that can seem to go on forever in a misguided attempt to sum up an artist’s entire sensibility.

Not every track connects. “Skyscraper,” the collaboration with Bono, goes painfully literal with an angel-devil scheme made only clunkier by the song’s weirdly perky beat. And the frankly emotional “Letter to My Son (Call Your Father)” didn’t need all the weepy violin to make its sobering point about generational trauma. But DMX sounds remarkably driven on “Exodus” — a man with life, not death, heavy on his mind.