Within the nineteenth century, being Ukrainian was typically a matter of selection. Ukraine’s city inhabitants often spoke languages apart from Ukrainian: principally Polish, generally German within the cities of Habsburg-ruled Galicia within the west, Russian within the cities of the Russian Empire, Yiddish within the Jewish populated cities on each side of the Russian-Austrian border. The vast majority of the nation’s rural inhabitants, in the meantime, spoke Ukrainian dialects and adhered to cultural traditions that we might these days acknowledge as sometimes Ukrainian. However what little proof we now have about their self-perception means that, within the absence of political rights, most recognized with their village, faith or the peasantry relatively than with a bigger nationwide neighborhood. Those that moved to the cities and managed to lift their social standing often discarded their rural dialects. They took up Russian and Polish, talking with heavy tongues within the first technology, whereas their youngsters largely assimilated into Russian or Polish-speaking city society.

When the Ukrainian nationwide motion gained steam in the midst of the nineteenth century, a few of its activists had been former villagers, little children of peasants or rural monks, who had not totally assimilated and retained a robust reference to Ukrainian-speaking rural tradition. However many weren’t. The patriotic students who gathered in Kyiv’s Ukrainophile circles throughout the 1860s and 1870s had been a motley crew united not by their widespread ethnic heritage however by political convictions. They shared a dedication to Ukraine’s peasants, whom the Russian state noticed as Little Russians, part of a bigger Russian nation. The Ukrainophiles disagreed. For them, these peasants had been the core of an autonomous Ukrainian nation, a nation with its personal language and tradition. Enhancing their lot would require the federalization of the imperial Russian state, liberating peasants from the burden of assimilation by instructing them in their very own Ukrainian language – a language that many Ukrainophile intellectuals didn’t know very effectively.

Ukrainophiles, not Ukrainophones

Maybe essentially the most spirited of Kyiv’s Ukrainophiles was Volodymyr Antonovych. A professor of historical past on the metropolis’s college, he initially got here from a Polish-speaking household. Raised on a noble property in rural Ukraine, he familiarized himself with the traditions of the Polish gentry, who noticed themselves because the cultural elites of the area and sometimes despised the Ukrainian-speaking peasants, perceiving them as ignorant and lazy. As a youngster, Antonovych was educated at a Russian-language college and studied on the universities in Odesa and Kyiv earlier than embarking on his personal tutorial profession. However Antonovych’s trajectory neither led him in the direction of the Polish nationality of his family nor towards assimilation into Russian imperial tradition.

An avid reader of French enlightenment philosophy, the younger pupil turned more and more within the lives of the Ukrainian-speaking peasantry, in whom he acknowledged a democratic ingredient of the area’s social order. He and his buddies donned peasant garments and started to hike throughout the countryside to study rural life; they started to see themselves because the peasants’ brethren in a separate Ukrainian nation. Patriotic Polish nobles weren’t amused. They mocked Antonovych and his buddies as chłopomani (peasant lovers) and accused them of being turncoats who had betrayed the Polish nation. In 1862, Antonovych penned a response, through which he proudly embraced this epithet:

I really am a ‘turncoat’. […] By the need of destiny I used to be born in Ukraine a member of the gentry. In childhood I possessed all of the habits of a gentry youth, and I lengthy shared all the category and nationwide prejudices of the folks in whose circle I used to be raised. When, nonetheless, I attained the age of self-awareness, […] I noticed {that a} man of the Polish gentry dwelling in South Russia had however two selections earlier than the court docket of his conscience. One was to like the folks in whose midst he lived, to develop into imbued with its pursuits, to return to the nationality his ancestors as soon as had deserted, and, so far as potential, by unremitting labor and like to compensate the folks for the evil finished to it. […] The second selection, for him who lacked ample ethical power for the primary, was to to migrate to Polish territory, inhabited by the Polish folks, so that there is perhaps one much less parasite […]. I, after all, determined upon the primary […].

Volodymyr Antonovych and his spouse Varvara in Ukrainian people attire, between 1850 and 1860. Picture through Wikimedia Commons

For Antonovych, then, serving the peasantry and assimilating their tradition was an ethical obligation for Ukraine’s elites. His textual content was testimony to an virtually religiously felt nationwide conversion – and certainly he did convert from Catholicism to Orthodoxy – in addition to a gospel of voluntarily chosen nationality. Having embraced Ukrainian nationality for political causes, Antonovych discovered the Ukrainian language and explicitly inspired others to do the identical. A few of his college students and buddies in Kyiv’s educated circles adopted his path. The Ukrainophile circle (Hromada) of the interval included many native Russian audio system, each current arrivals from Russia and descendants of assimilated native households, but additionally the Jewish lawyer Vladimir (Volodymyr) Berenshtam and the half-Swiss economist Mykola Ziber (Niclaus Sieber). Lots of them by no means totally mastered the Ukrainian language, talking it conspicuously with fellow Ukrainophiles however resorting to Russian to debate extra sophisticated matters. Nor had been situations favorable for switching to a language that the Russian imperial state repeatedly banned from the press and faculties, leaving its audio system open to authority investigations.

Versatile identification

After all, the alternative place was additionally potential and plenty of socially cellular Ukrainians assimilated to Russian imperial tradition. Some even turned leaders of the empire’s burgeoning Russian nationalist motion. Such acutely aware selections of nationality weren’t distinctive to Ukraine. In Bohemia and Moravia, as an example, some German-speakers additionally recognized as Czechs and studied the Czech language to develop into unambiguous members of the nation (and vice versa). However in Ukraine, the place the language of the peasantry was associated to these of the dominant neighbouring Russian and Polish cultures, and Russians and Ukrainians shared the Orthodox faith, nationwide conversion and assimilation in all instructions was simpler than elsewhere.

The phenomenon was widespread sufficient for contemporaries to note and remark upon. For example, the Polish literary scholar Jerzy Stempowski, who grew up in Podolia within the early twentieth century, later gave the next ironic but perceptive account of nationality points throughout his youth:

The sons of Poles generally turned Ukrainians, the sons of Germans and Frenchmen turned Poles. […] ‘If a Pole marries a Russian lady,’ my father used to say, ‘their youngsters are often Ukrainians or Lithuanians.’ […] In these occasions, nationality was not an inevitable racial destiny however largely a matter of free selection. This selection was not restricted to language. […] every language carried historic, non secular, and societal traditions; every fashioned an ethos etched by centuries of triumphs, defeats, desires, and sophistry.

From enforced nationality to citizenship

The age of mass politics, particularly the onset of Soviet rule, essentially modified this case. Though purportedly based mostly on class rule, the Soviet state institutionalized nationality each territorially, with nationwide republics, and individually, making nationality an unalterable and inheritable class fastened in passports. In an age of totalitarian claims to characterize primordial nationwide collectives, nationality was more and more, in Stempowski’s phrases, ‘an inevitable racial destiny’. In contrast to within the nineteenth century, residents had an official nationality that they retained even when they totally assimilated to a distinct language. Tens of millions of assimilated Russian audio system in Ukraine had been labeled by the state as Ukrainians, and plenty of of them additionally noticed themselves as such.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, impartial Ukraine abolished the passport class of nationality. As a substitute, the state solely acknowledged citizenship and society’s conception of the Ukrainian nation shifted in a civic route. Ethnic background turned a much less salient class, as many individuals from ethnically Russian households both ceased to determine as Russians or perceived themselves as Russian-speaking residents of Ukraine. Sociological surveys present that the proportion of people that recognized primarily as Ukrainians elevated steadily from the Nineties by way of the 2010s. On the identical time, most Russian-speaking Ukrainians didn’t drastically change their linguistic habits.

Wilful conversion

The Euromaidan protests of 2013-2014 and Russia’s aggression in opposition to Ukraine’s territorial integrity have additional rallied Ukrainians across the flag. Confronted with an existential menace, hundreds of thousands of individuals of various ethno-linguistic and non secular backgrounds have declared their loyalty to Ukraine, not least as a result of they see it as a extra democratic and liberal various to Putin’s ‘Russian World’. Satirically, the shift towards a extra civic conception of Ukrainian nationhood has been accompanied by an inclination towards monolingualism. As within the nineteenth century, some Russian audio system have consciously switched to the Ukrainian language for political causes.

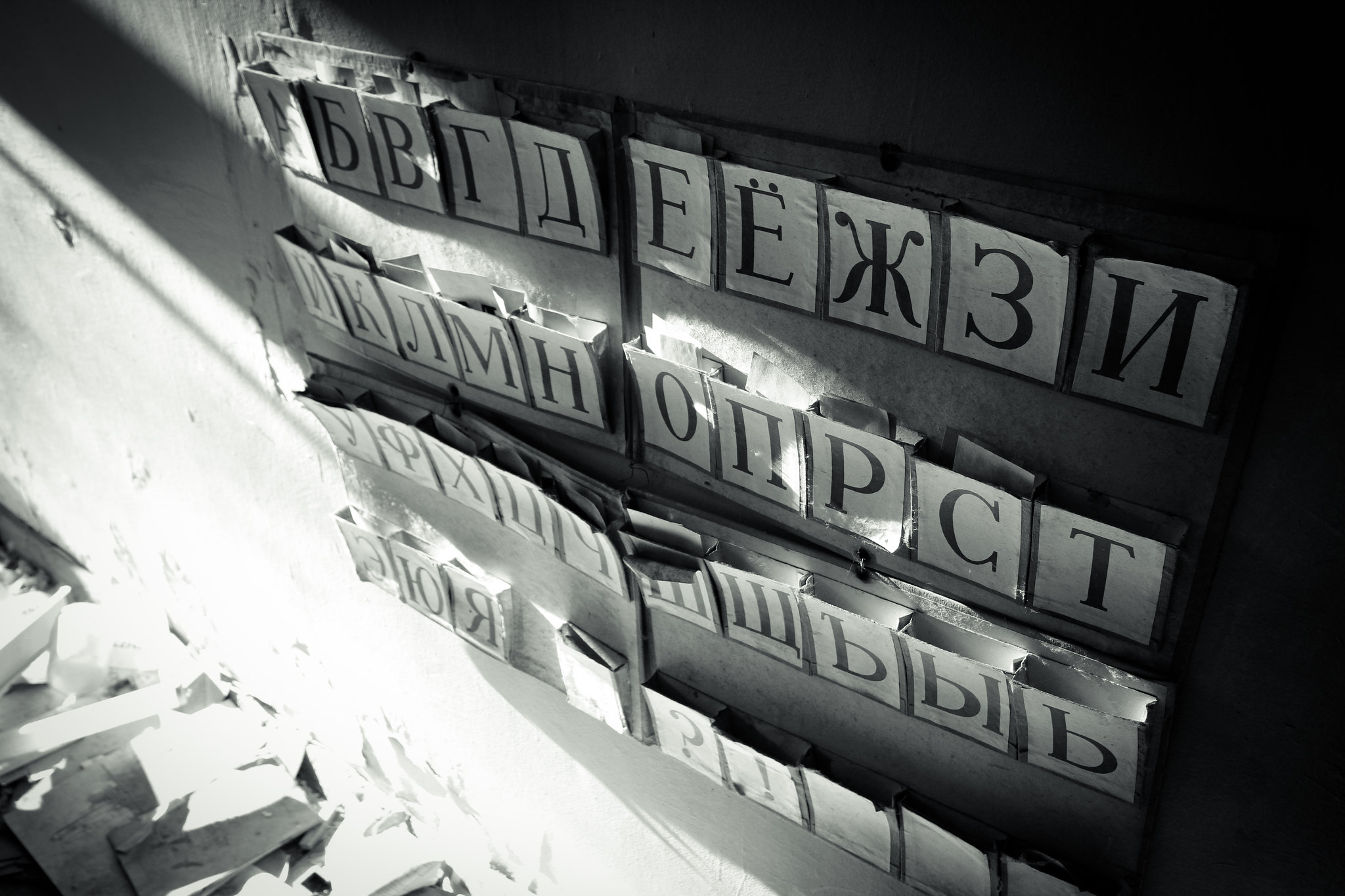

Ukrainian alphabet, deserted college in Pripyat, Ukraine. Picture through Flickr

This improvement is intently linked to the Putin regime’s instrumentalization of Russian and its spurious declare to be defending the rights of Russian audio system throughout the globe as justification for its conflict in opposition to Ukraine. My host in Kyiv’s charming Podil district throughout my most up-to-date go to in 2019, a sixty-year-old man who grew up in a Russian-speaking household, was a living proof. He wouldn’t communicate Russian anymore, he instructed me in Ukrainian with a discernible Russian accent. He felt virtually bodily incapable of enunciating the identical phrases as Vladimir Putin.

A well-known instance is Volodymyr Zelens’kyi, Ukraine’s president, who grew up in a Russophone household and made his profession as a comic in Russian. By now, his linguistic Ukrainization is so full that he generally – maybe performatively – asks his aides to assist translate a time period into Russian when giving an interview to Russian-speaking media.

Many younger Ukrainians see selecting Ukrainian statehood and its language as a symbolic rejection of the political paralysis of the post-Soviet sphere. Creator Sasha Dovzhyk, for instance, has lately described her ‘conversion’ from being a Russophone youth within the southern Ukrainian metropolis of Zaporizhzhia to changing into a Ukrainian-speaking mental. For Dovzhyk, it was the Euromaidan protests that sure her to the venture of Ukraine’s democratic future versus Russia’s homophobic authoritarianism. The expertise of a robust anti-authoritarian motion provided perspective on what she now perceives as a language of imperial oppression: ‘Such a language’, Dovzhyk writes, ‘refines stratifications, enfeebling one’s thought and finally making one shudder on the thought of expressing anger on the higher-ups.’

Nationality over language

Not all patriotic Ukrainians go so far as Dovzhyk of their rejection of the Russian language. For a lot of Russian audio system, Ukrainian stays a symbolic marker of identification relatively than a daily technique of communication. However analysis by sociologists reminiscent of Volodymyr Kulyk means that politically motivated modifications of language at the moment are a widespread phenomenon within the jap and southern areas of Ukraine. Granted, declarations of Ukrainian being both a ‘native tongue’ or a ‘language of comfort’ shouldn’t all the time be taken at face worth. Given the present scenario, some could declare to make use of Ukrainian greater than they really do as a result of they take into account it politically acceptable. Nonetheless, the widespread bilingualism in Ukrainian society makes it potential for a lot of Ukrainians to change between languages comparatively simply, even when their Ukrainian should embody occasional Russian phrases or calques on Russian expressions. Even monolingual Russian audio system within the nation are aware of Ukrainian resulting from frequent publicity to the language, whether or not on tv or in encounters with Ukrainian-speaking neighbour.

When Vladimir Putin got down to ‘liberate’ Russian-speaking Ukrainians, he utterly misunderstood their priorities. Most had been loyal residents of democratic Ukraine and had little curiosity in changing into topics of Putin’s kleptocratic dictatorship. To many, this was extra vital even than persevering with to talk their native language. The way forward for the Russian language in Ukraine is subsequently unclear. Tens of millions of Ukrainians will probably proceed to make use of Russian at the least in some conditions whereas remaining loyal residents of the Ukrainian state. Nonetheless, a lot of them might be pleased to have their youngsters educated in Ukrainian solely. Due to this fact it appears probably that youthful Ukrainians, who will all the time strongly affiliate Russian with the felony Putin regime, will develop into essentially the most Ukrainain-speaking technology in Ukraine’s trendy historical past. To them, being Ukrainian and talking Ukrainian will seem to be the obvious factor on the planet. In the intervening time, nonetheless, there’s a robust part of option to Ukrainian identification and language, as there was within the nineteenth century.

This text has been printed as a part of the youth venture Vom Wissen der Jungen. Wissenschaftskommunikation mit jungen Erwachsenen in Kriegszeiten, funded by the Metropolis of Vienna, Cultural Affairs.

Supply hyperlink