Hate It or Love It

Leaks have moved from burned CDs to buried chat rooms, but one constant remains: for rappers, they’re a blessing and curse.

Words: Stacy-Ann Ellis

Editor’s Note: This story originally appeared in the Winter 2020 issue of XXL Magazine, on stands now.

BUY XXL MAGAZINE’S WINTER ISSUE

“Whoever got his songs better sell ’em now before they end up on the album. I’m buying btw.”

This was one of the first responses in an eight-page Leakth.is megathread dedicated to Pop Smoke’s posthumous debut album, Shoot for the Stars Aim for the Moon, the effort bookending the slain Brooklyn rapper’s legacy. Leakth.is touts itself as “the best music leaks forum on the web.” Another Pop Smoke fan on the forum wrote, “Im conflicted…I dont wanna fuck up his release so I’ll probably leak 1 song, then sell the rest after his album (whatever didnt get dropped).” This was May 14, 2020, a full month before the project’s original due date of June 12. By the time the album finally dropped on July 3—it was pushed back out of respect for America’s long-delayed race reckoning—these fans would have already heard it and begun petitioning for the next artist’s music in the vault.

At this point, leaked music has become unavoidable, and hip-hop has almost exclusively bore the brunt of it. Think about it: How often do we hear about leaked music in rock, pop, country or R&B? Cameron Capers, an Arista Records A&R, Blackwax management company cofounder and former Parkwood Entertainment employee, notes how structural differences in pop and country minimize the occurrence of leaks. “The producers and writers, they have small communities, and if you’re not in that community, they don’t really let a lot of new people in,” he says. “Whereas hip-hop and rap has always been a culture that’s inclusive of everyone, and everyone feels like they can be a part of it.” And more hands working on rap records equals more open doors for the goods to get out.

Few heavy hitters in hip-hop have been spared from leak culture. Eminem rushed writing sessions for his 2004 album Encore after he experienced leaks during the recording process, and Lil Wayne admitted albums like 2008’s Tha Carter III spread after leaving his CDs playing in the car. Kanye West famously lashed out at the internet when “Lost in the World” and “All of the Lights” from his 2010 album, My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy, escaped the vault. ’Ye had previously endured a months-early leak of his 2004 debut album, The College Dropout. In May of this year, Drake made use of a moment when he dropped Dark Lane Demo Tapes, a 14-song compilation of old leaked songs and SoundCloud loosies. However, the last couple years have been particularly unforgiving for the newest crop of powerhouse rap stars. Artists like Juice Wrld, Young Thug, Playboi Carti, Lil Uzi Vert and 6ix9ine, among others, have felt it harder than most.

6ix9ine delayed his 2018 debut studio album, Dummy Boy, after he was arrested on racketeering and firearms charges on Nov. 18, 2018, but less than a week later, the entire 13-track project surfaced online. His team ended up dropping the album a few days later as a result of the leak. Last year, over 30 unreleased Young Thug songs, including features with Future, Gunna, Big Sean and Offset leaked online. Just one month after Juice Wrld’s tragic death in 2019, about 26 of his unreleased songs were posted to SoundCloud under the username 999 WRLD without his estate’s consent. Juice continues to be one of the new-gen rappers most heavily affected by leaks since his popularity increased.

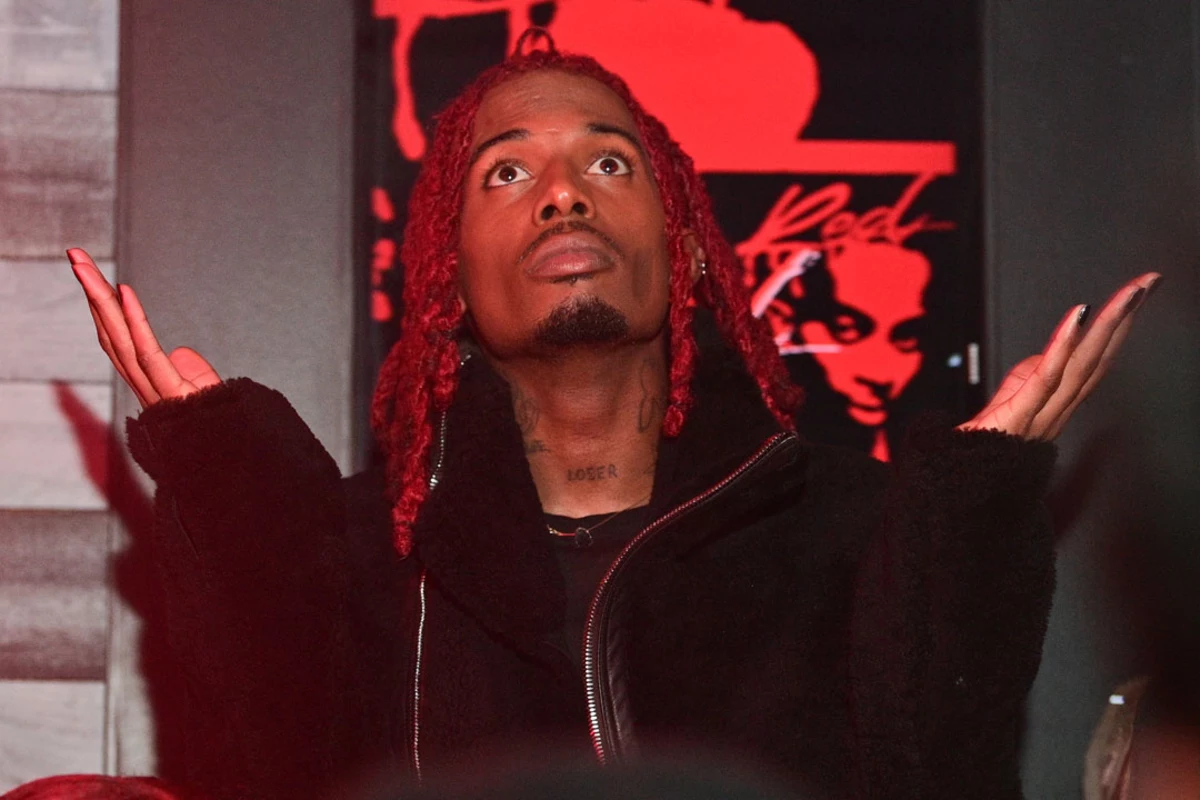

Before Lil Uzi Vert’s long-awaited Eternal Atake arrived on March 6, 2020, a string of 2019 leaks, mixed with label drama stemming back to 2018, delayed the album by nearly a year. And when it comes to Playboi Carti, his fans will likely know many of the verses on his long-awaited Whole Lotta Red album before it even drops because the leaks of his songs are rampant. “How the fuck y’all niggas know that song?” he quipped at The Lyrical Lemonade Summer Smash in Chicago in 2019, after performing a new song called “Neon.”

Their leak streak makes sense. “Those are all prolific artists in terms of recording a lot,” offers Justin Grant, Director of Digital Marketing at Atlantic Records. “They are always in the studio and creating at a really high rate, so there’s just more material out there in general that can be leaked.” But how does coveted material, thought to be guarded by labels, teams and the artists themselves, actually get in the hands of faceless strangers?

The first time Smokepurpp got hacked was in 2016, when someone with his phone number, government name and the address linked to his phone called T-Mobile to request a SIM card. SIM swapping, hacked emails and devices, and website security breaches are some of the most common ways sealed songs make their way onto fans’ phones. “If somebody knows that I have, like, a really special song, they know they can’t hack me, but they’ll probably try to hack somebody’s phone who I hang out with and get the song from there,” he said in June on XXL’s Hip-Hop Moments of Clarity podcast, as if it’s an unstated rite of passage. “You know how it goes.” It’s something every artist must seemingly go through at least once.

Record labels, rappers and their teams have made efforts to increase the security of their sessions. Preventive measures like previewing music for potential business partners over the phone versus Dropbox, no longer storing songs as voice notes, getting files directly after a recording session, and requesting that unfamiliar engineers delete their copy can help. But sometimes it’s not about the security; it’s about the circle. “There’s times where a producer is in a session with an artist and it just comes down to them not being a very good person, having access to those files and then putting them up for sale online,” Grant shares. “Then you see that random kid in Wyoming, like, ‘Yo, I got all of these unreleased tracks.’” Rappers often roll with robust entourages, so it’s hard to tell who is keeping an artist’s work close to the chest, and who’s looking to put extra money in their pocket.

According to Cameron Capers, whose producers he enlists have created music for Cardi B, Lil Nas X, Juice Wrld, Bryson Tiller, Cordae and more, having mix-and-match recording sessions complicates things. “Most of those artists make tons of music in different studios, and I don’t know if there’s a streamlined process for the way they create,” he maintains. “A lot of them want to go to the studio and let out what they need to let out.”

R.I.P. to the days of stockpiling bootleg CDs and buggy pirating programs like LimeWire and Napster. Nowadays, finding leaks can be as simple as a quick Google search and download link. For low hanging fruit, there are small scale operations such as TikTok, Twitter or Instagram accounts like RareRapLeaks, which gained nearly 9,000 followers in its first six months. The page, which was started on Dec. 8, 2019, the very same day of Juice Wrld’s passing, has over 17,000 followers now. “This account grew fast,” says the 18-year-old creator of RareRapLeaks, who has withheld their name, via an Instagram DM. “My first post was Juice Wrld and YNW Melly’s ‘Suicidal.’” According to the RareRapLeaks creator, the followers on the account clamored after all leaks related to JuiceWrld, Lil Uzi Vert and Playboi Carti. “There was a snippet out at the time and I posted it with zero followers and it gained a lot of views.” Instagram accounts like this link out to spreadsheets and Google Drives with organized folders and a barrage of songs to cherry-pick from if you have the patience to scroll through. However, these harmless offerings are not for sale.

Dig a little deeper and you’ll find Reddit threads, Leakth.is forums and servers on Discord, a group-chatting app popular in the gaming community. Here, not only do people trade and talk about swiped music, but it’s also where they sell them. “The songs that are being sold for money are exclusive songs, meaning no one else has them,” says the owner of the RareTrackz Instagram account, who wished to remain anonymous. The account now boasts more than 85,000 followers. “If it’s a track by an artist with a big audience, it will be expensive. The full song isn’t out at that point, so people will group-buy the song for it to leak in its entirety, which is when it gets posted. Trades happen where exclusive (not leaked) tracks are traded. Private buys are another, where someone will buy a song and vault it, to keep something of value to themself.” Group-buys in this situation are the act of users coming together to collectively pay for the leak of the song with their combined purchasing power.

Conversations about acquiring new leaks start in the forums, but transactions happen on the servers, so you have to work a little harder. Leakth.is and Discord both require accounts to view leak threads, but it’s not enough just to have them. Accounts must be active and engaged on the platform’s discussion boards—reacting to posts and leaving at least 25 published messages—to unlock the Marketplace, which houses the Verified and Unverified Selling/Trading, Groupbuy and Buyer’s Bay forums. Song verifications, for anything worth over $200, are vetted through six administrators, moderators and “middlemen” with different claims of expertise. And after going through the process of group-buys for unreleased Drake and Don Toliver cuts ourselves (for research purposes only), it’s clear that lots of internal thought has gone into finding ways to keep scammers out as the leaks—and sales attached to them—come in.

Here’s an example: Toliver’s “High No More,” a three-minute, 12-second song circulating the internet this year, gets posted in the Group-buy forum, priced at $475. A quick click in the thread provides an invite into a Discord server with 23 other interested buyers, where the seller, moderator and administrator are present to facilitate a fair purchase. Discord servers are a lot like Slack channels. There are chats for information and how-tos, announcements, song verification snippets, general chatter, making pledges and monitoring payment. The pledge chat is where users will promise the amount they’ll contribute towards a buy (numbers ranged from $5 to $150) before the ask amount is met and payments open up. After pledging, it’s a waiting game to hit the target. Sellers can lower the cost if they’re not confident they’ll hit the goal. When $395 out of the $475 is pledged, the seller directs buyers to a now-opened payment channel, where the receiving account info is shared. Most transactions are handled with cryptocurrency—Venmo, Cash App, Bitcoin—but some accommodating mods may greenlight a Paypal payment. Screenshots of money transfers go to the unlocked Payment Screen Shot channel (which all disappear minutes later for security). Once all funds are in and buyers migrate to the Paid Chat channel, the moderator shares a download link to the full Don Toliver song.

Then there are higher profile buys. Drake’s “Stay Down” featuring a Busta Rhymes verse and J Dilla production will obviously have a steeper going rate—$1,025. Pledges made it to $500 within two days, but facilitators, seemingly nervous about hitting the goal, started taking payments at $700, more than $300 away from the goal. Big buyers nudge users to join a $5 train, upping their pledges to hurry things along. There are “pay up” tagging sprees and offers to spot those who don’t have it. By the end of it, the desired amount is overpaid by $20, and the song is released straight into a general Leakth.is thread for the masses to download and enjoy for free.

There’s an undeniable thrill to leaking music for both buyers and suppliers, a thirst to gain followers, clout, the right to say “First!” or collect a piece of music history. But, all this thrill-seeking is a pain in the ass for the teams who have to chase the unauthorized work after it’s out.

The takedown process usually starts once the artist’s management contacts the label. Most labels have internal services, legal and content protection teams dedicated to pulling down illegally posted material. They’ll do things like rope in RIAA to report piracy and put out copyright notices like a DMCA to remove links from websites, then utilize fingerprint blocking on YouTube and SoundCloud to automatically prevent future uploads. Removing a leak is one thing; finding its origin is another. From experience, that path seldom bears fruit. “It’s a lot of work to trace it, so it’s usually only really pursued if it’s a really high-profile song or a high-profile feature,” Grant reveals. “Nobody ever seems to actually know the source. There’s a few select examples of when we’ve found the exact person who’s leaking the music. Cool, it was this person in the studio or this person’s friend, but it’s never been easy to trace the source of the leak.”

While leaks have proven to boost numbers in some instances, those illegally posted to streaming services can rob artists of their earnings. According to Rolling Stone, Lil Mosey’s then-unreleased “Blueberry Faygo’’ was uploaded to Spotify in December of 2019, at least eight times under different users and titles (“Blueberry Fweigo,” then “Blueberry Fejgo,” “Blueberry Fergo,” “Burberry Faygo,” “Blueberry Fanta”). Not only did the miscredited song top Spotify’s U.S. Viral 50 chart—which tracks the fastest-growing songs on the platform—but it also garnered at least 22 million initial streams in January 2020, none of which went towards Mosey’s name (or his pocket). He officially uploaded the song on his own account a month later and at press time, the real “Blueberry Faygo” has been streamed over 612 million times.

“If the music has been released by another entity and you want it taken down and properly released under your name, in a lot of cases, you may not be able to get those streams back,” explains Mike Hamilton, Director of Commerce for Epic Records, who works directly with streaming platforms like Spotify, Apple Music, Tidal, Amazon and Pandora when it comes to rolling out an artist’s song or project. “That’s the case where you absolutely are impacting this artist’s livelihood.”

Young fans think they’re just taking opportunities for income from wealthy artists and the labels that back them, but they’re not the only ones who suffer. Leakers ruin revenue and advancement opportunities for producers and songwriters, too, who often get the short end of the stick. “The artists can still go tour and make money on that song,” Capers stresses, “but everyone else who’s involved with the song creatively can’t make money if you’re selling it illegally.”

As inconvenient and frustrating as leaks can be, it’s quietly understood that they’re not always bad news. The buzz around leaks, especially when they’re close to release dates, prepares fans for the new material and makes work for their marketing teams a lot easier. “For somebody like Playboi Carti, who hasn’t put out a body of work in a really long time, but stays relevant…it keeps their name out there without him actually having to drive the conversation,” Grant states.

In July of 2020, a video began circulating on the internet in which producer Jetsonmade talks with a buyer who’s offering $17,000 in Bitcoin for Playboi Carti’s unreleased music. The buyer plays a snippet of a song for the producer, who tells the man he doesn’t have that track but does have access to another one. After receiving both backlash and excitement from eager fans wanting the rapper’s new music online, Jetsonmade denied that he was allegedly selling any of Carti’s songs. “Dat video y’all keep posting is CAP,” he wrote on his Instagram Story. “i was definitely trolling.”

“From a marketing perspective, sometimes I almost expect a leak,” a major label product manager, who has asked to remain anonymous, says over the phone. She uses leaks as opportunities to confirm or deny rumors about features and release dates. “It’s really just getting ahead of the curve for us and advising artists on having that strategy and plan in case there is a leak.” But whether labels have a handle on them or not, leaked songs force artists to make major, and sometimes unfair, decisions about the fate of their work.

Back to Smokepurpp, one of the rare artists who’s been open to speaking on this topic overall. The Florida native knows firsthand how much leaks damage opportunities. His song “No Problem” featuring Kanye West was originally meant to appear on his 2019 debut studio album, Deadstar 2, which leaked several times before its release date. However, the track never made the final cut. Purpp says that Kanye’s camp chalked it up to a change in artistic direction—the song’s explicit content negated ’Ye’s Christian pivot—but Purpp feels the leak put the nail in the coffin. “I’m not gonna lie, I was kinda sad about it because Kanye is one of my favorite artists,” he admits wistfully. “Having a song with Kanye was like a huge milestone for me. For somebody to just leak it, it kinda hurt me a little bit.”

In a Leakth.is discussion thread, a curious user polls the room: Leaks you wouldn’t mind being released. He offers up his picks first: “Ghost” by Trippie Redd; “Molly,” “Neon” and “Headshot” by Playboi Carti; “Fast and the Furious” by Young Thug and Offset. But overwhelmingly, the sentiment is that once a song gets leaked, it should be scrapped. Period. “If it’s leaked, never release it. Fuck we want it out for when a brand new song can have its spot instead?” a now-banned user spits. “I’m completely against leaked songs getting released,” says another.

Dissenting voices weigh in. “That’s like rewarding leakers with new music, lol. If you leak music and listen to it, that’s on you and you’re not entitled to any new songs,” one user counters. “People want songs to leak that are confirmed to be on an album…,” another adds, “than [sic] they complain if the song still ends up being on there.”

The exchange is proof that, to a degree, leakers are aware of how much taking and demanding music they feel entitled to as stans stings the very artists they love. “There’s a weird relationship in that the artists would not be where they are without their fan base,” Hamilton conveys. “Some of them succumb to the pressure of, ‘We have to rush this out because my fans are hitting me about it.’ But these are still artists. You have to give them the opportunity to create on their own time.”

A fact that should be respected.

Check out more from XXL’s Winter 2020 issue including our DaBaby cover story, an introduction to DaBaby’s Billion Dollar Baby Entertainment label roster, an interview with South Coast Music Group founder Arnold Taylor, who discovered and signed DaBaby, one of King Von’s last interviews, how the coronavirus changed hip-hop, we catch up with Flipp Dinero in What’s Happenin‘, we talk to Rico Nasty about rediscovering who she is as an artist, Marshmello reveals the rappers he wants to work with in Hip-Hop Junkie, Show & Prove interviews with The Kid Laroi and Flo Milli, and more.

See Photos of XXL Magazine’s Winter 2020 Cover Shoot With DaBaby