Courtesy of the artists

It’s impossible to overstate how golden hip-hop shone in 2017 — the shattered Billboard records, the most-streamed genre recognition from Nielsen. Industry hype aside, rap reflected our collective conscience, and national crisis, like never before. While the power of playlists (and the ability to juke streaming stats with song loops) set new standards, the long-play album remained the definitive format for artists intent on making timeless creative statements. And artists got pretty (DAMN.) creative within those confines.

Jay-Z and Tyler, the Creator averted respective midlife and quarter-life crises with their most mature confessionals to date. GoldLink and Open Mike Eagle erected memorials to the erased cultures, and cribs, of their upbringing. Lil Uzi Vert and Future went hyper-emo over loves lost and loathed. Big K.R.I.T. and Cyhi The Prynce transcended the traps and clichés of Southern rap. Kendrick Lamar exposed his prophetic struggle on an altar of self-sacrifice. And Rapsody reigned supreme over nearly everybody.

In a year this robust, it would be easy to make an exhaustive list of the best releases. Indeed, the Internet is chock full of them. But hip-hop did not ascend to new heights in a vacuum. It’s sonic uprising happened amid a national backdrop of political upheaval, racial discord, violent demonstrations and revelatory reckoning around the systemic abuses of power and gender inequality that hits so close to home in this genre.

In hip-hop, as elsewhere, the personal is always political. Where you’re at, so to speak, and how you choose to cultivate and represent that space – whether real or imagined — matters.

It’s as true today as it was 15 years ago, when academic Murray Forman published his book The Hood Comes First: Race, Space, and Place in Rap and Hip Hop. “The music I was listening to was always articulating place-based identities — whether it’s Hollis, Queens or Brooklyn [or] South Bronx,” Forman recently told me, recalling his original inspiration for the book. He chose to look at this “defining aspect of the sound” in a “larger, deeper sense,” he says, “not just as a hip-hop thing, but a thing about racial identities and the way places get attributed to certain people in society.”

In the same spirit, NPR Music’s roundup of the year’s 21 best hip-hop albums is themed around the politics of race, space and place. Among 2017’s best LPs, these are some that challenged or complicated America’s record on race, detailed a strong sense of place while critiquing widespread cultural erasure, or broke conventions of genre, gender and identity within the space of rap itself. — Rodney Carmichael

Vince Staples, Big Fish Theory

The feminist essayist and poet Adrienne Rich once wrote that “an honorable human relationship — that is, one in which two people have the right to use the word ‘love’ — is a process, delicate, violent, often terrifying to both persons involved, a process of refining the truths they can tell each other.” She was talking about relationships between women, so I hope you’ll forgive me for applying her idea to all people who have had to learn to lie as a survival mechanism: Vince Staples’ album of tear-jerking club bangers is the process of love in action. This is a record that creates space for truths: The way you talk about genre, if you’re not careful, is probably a lie, and the history of electronic and house music is a black history.

It is also an album of love songs. No one is calling them love songs because Staples’ lyrics, much like the beats they’re presented with, don’t follow the conventional scripts. But when, over a bass line that goes hard enough to bust unsuspecting speakers, the song “745” issues the confession: “This thing called love real hard for me / This thing called love is a god to me,” it feels heart-wrenchingly romantic. He is not casting a value judgment on that struggle with love. “I don’t think anything’s good or bad,” he once said. Instead, he is telling a truth. — Jenny Gathright

[embedded content]

YouTube

Quelle Chris, Being You Is Great, I Should Be You More Often

Quelle Chris is no shrinking violet; in fact, the stereotype of indie-backpackers-as-schoolmarms hasn’t held true since the Dillatroit/Madvillain/Okayplayer wave of the mid-aughts. He calls rival rappers “clones” on “The Prestige” (which also boasts an incredible soliloquy from Jean Grae). But he hungers for the spoils of lyrical warfare, too. On “I’m That Nigga,” he brags about sporting the baddest ladies, “each city, each town.” The Detroit-bred nomad, who has briefly claimed residence in cities from Oakland to Brooklyn, doesn’t try to resolve his inner contradictions. He doesn’t hide from them, either. Some of the best songs on Being You Is Great, I Should Be You More Often — the illustrated cover depicts him as mirror images, one frowning and the other with a toothy grin — find Quelle sifting through his thoughts. “Feels like my birthday today, and those are the worst days / If it’s a race for the end, then why come in first place?” he raps on “Birthdaze.”

Stuffed with cameos by sundry luminaries of the hip-hop underground, this is an ideologically messy gem, made coherent by beats chock full of odd samples, produced by Quelle and others; and his crusty, sharply self-aware performance. — Mosi Reeves

[embedded content]

YouTube

Joey Bada$$, ALL AMERIKKKAN BADA$$

Joey Bada$$’ sophomore album roils with indignation, sadness and confusion, wrestling with political themes (police brutality, white supremacy and black identity) in his most thematically tight project yet. Rappers exploring the plight of blackness in America is hardly new, but there is something about this particular project, having been released in a period that’s seen the resurgence and relative normalization of neo-Nazism and white supremacy, that feels especially resonant and radical.

Now, when Joey raps “leave us dead in the street to be organ donors” in “LAND OF THE FREE” it reads like a headline, and “Y U DON’T LOVE ME (MISS AMERIKKKA)” is less a simple question and more a desperate attempt to understand racially biased attacks. ALL AMERIKKKAN BADASS is one of the year’s most outspoken records, with its message planted proudly at the forefront. Critics of the record would say that it’s a bit too on the nose; but perhaps, that’s the only way the message can be heard. — Steffanee Wang

[embedded content]

YouTube

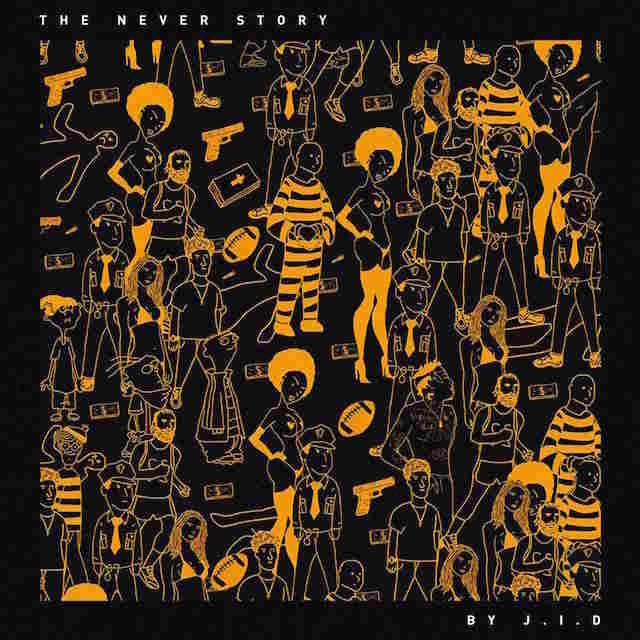

J.I.D., The Never Story

J. Cole once revealed in an interview that he had aspirations of signing Kendrick Lamar to his Dreamville label. As Cole tells it, he heard K. Dot spit live for the first time at a L.A. house party in 2010 and was immediately impressed. Of course, his pipe dreams were quickly dashed — Kendrick was already signed to Top Dawg Entertainment at the time. But, fast forward seven years, and Cole might just have gotten his wish for a rap star with J.I.D. Since announcing his signing to Dreamville in February and releasing his slow burn of a studio album The Never Story in March, the Atlanta MC and Spillage Village member’s LP has proven to be one of the strongest rap debuts of 2017.

There’s something playful yet stern about J.I.D’s delivery. Maybe it’s his tone, a jittery, almost-cartoonish pitch with just the right weight of believable bass. And J.I.D’s ability to bend and distort his original voice for the purpose of telling different story perspectives is part of the reason he draws comparisons to both K. Dot and Cole. On “Never,” he recalls his times of survival and strife over wild beats by Christo and Childish Major. On “Hereditary,” he runs through a dialogue about a self-sabotaging relationship accompanied by piano and electric guitar.

Clocking in at 40 minutes, The Never Story is agile in every sense of the word. With topics ranging from broken families to trust issues, J.I.D.’s debut is pegging him as a diamond in the rough of Atlanta’s syrup-soaked trap scene, while earning him praise from some of rap’s best. — Sidney Madden

[embedded content]

YouTube

Princess Nokia, 1992 Deluxe

If you listen closely to Destiny Frasqueri’s 1992 Deluxe, you might notice a thin layer of grit in the sound. It’s a welcome abrasion. In fact, it’s what gives Frasqueri’s 2016 mixtape — extended and re-released this year as her debut LP — an autobiographical realness that makes me imagine little Destiny romping through chain-link basketball courts, rapping these tracks quietly to herself.

1992 Deluxe is Frasqueri’s celebration of New York City and all those within it that don’t fit into society’s mold of respectability. In “ABCs of New York,” this includes the ghetto girls and single moms, the role models of her childhood. “Brujas” pays tribute to the African diaspora, reframing trauma as a spiritual superpower. In literature (remember The Crucible’s Tituba?) and history, witchcraft was an accusation pinned against black women that often ended their lives. This track subverts the narrative as it embraces spells and hexes, built upon traditional Yoruba spirituality, as the antidote to white supremacy: “I’m that Black Native American, I vanquish all evil.” Dizzying in its power and menacing in its message, “Brujas” is a neat thesis for 1992 Deluxe: “Talk shit, we can cast spells.” — Steffanee Wang

[embedded content]

YouTube

Smino, blkswn

There’s never been a shortage of talent amongst rappers from St. Louis. The city has always beamed with pride whenever an MC from the Show-Me State achieved success — from local pioneer Sylk Smoov to international superstar Nelly, who ultimately put the city on the map, we’ve eternally championed these artists. But unlike such cities as Atlanta, Houston and New Orleans, the floodgates never opened and the wider world has only been treated to such unique perspectives intermittently.

North St. Louis native Chris Smith Jr., aka Smino, migrated to Chicago in 2010 to get what his hometown couldn’t offer him at the time — a solid musical infrastructure. But home was never far from mind: He released his debut album, blkswn, on Tuesday, March 14 — 3/14 or 314 Day, an unofficial holiday in St. Louis. The album personifies the updated culture of the city, touching on social struggles (“Long Run”, “Amphetamine”), but thriving in celebration and youthful pleasure on tracks like “Netflix and Dusse” and his breakout ode to black women, “Anita.” The harmonious nature and textures of blkswn are far beyond what a novice rapper would be able to pull off; a testament to his church background and musical lineage. It remains to be seen whether Smino will become the trailblazer of an imminent STL movement. But his moment is right now, so let’s toast to that. — Bobby Carter

[embedded content]

YouTube

Billy Woods, Known Unknowns

Billy Woods’ sixth solo album — not counting side projects like Armand Hammer, a pairing with Elucid that produced Rome last fall — sounds like vintage underground New York, with seamy, claustrophobic beat booms that resemble clogged subway arteries. Woods plays the role of a rap enthusiast so immersed in the culture that he can’t see doing anything else. On “Groundhogs Day,” he whimsically describes a day of getting up, smoking weed and trying to make his perpetually underfunded career work. Tracks like “Snake Oil” and “Everybody Knows” reveal a mind that couches political insights in pulpy metaphorical language. “They know the plates on your mama car / They know where the hooptie parked,” he raps on the latter in a conspiratorial, paranoid tone over producer Blockhead’s flurry of deadpan piano notes. “They know who you are.” A veteran producer whose musical tricks hail from the DJ Shadow school of baroque, drum-heavy instrumentals, Blockhead helps sustain Woods’ best work to date, especially on tracks like “Bush League,” which sounds like an Afrobeat compact disc stuck on repeat. — Mosi Reeves

[embedded content]

YouTube

Big K.R.I.T., 4eva Is A Mighty Long Time

There’s a song on Big K.R.I.T.’s double LP, 4eva Is A Mighty Long Time, that encapsulates why this point in his career has been such a long time coming. Titled “Drinking Sessions,” it is, as the name suggests, a cathartic release that finds K.R.I.T. exposing his mortal wounds and insecurities with zero inhibition — from the dreams he found just out of reach in an industry built on illusion to the emotional toll he endured chasing success to the point of sacrifice. “Everybody tryna die young, but who gon’ talk about life,” he hollers, as the woozy bass line lumbers in like a drunken funeral dirge.

After years of creative compromise inside the major label system, Mighty Long Time finds K.R.I.T. back in rare form, but also better for the wear. Those Def Jam budget restrictions that forced him to give up his sample-based approach to production made him expand his chops with live instrumentation and collaborative producers who could recreate the soulful palette he displayed on early self-produced mixtapes K.R.I.T. Wuz Here, Return Of 4eva and 4eva N A Day. As he does on those classics, the Mississippi representative is still mapping his personal journey and coming to terms with the contradictions that make him uniquely human. But the burden of his blues is offset by an undying faith that makes forever seem more like a promise than an impossibility. — Rodney Carmichael

[embedded content]

YouTube

Migos, C U L T U R E

It feels like it’s been years since Migos released C U L T U R E at the beginning of 2017. Since then, the trio has effectively infiltrated the mainstream’s field of vision, collaborating with Katy Perry, Calvin Harris, Frank Ocean and countless others. The lead single from the album, “Bad and Boujee” with Lil Uzi Vert (whose own Luv Is Rage 2 you’ll find below), was inescapable and stayed on the Billboard Hot 100 for 36 weeks. Donald Glover thanked the group in his Golden Globes acceptance speech, comparing them to the Beatles. Migos performed on Ellen, one of the most surreal events of the year. Thinking back on it all, it was perhaps predestined that the record came to us at the start of the year, quietly asserting itself as the game-changer that would alter the cultural landscape as we knew it.

The album’s enthusiastic reception makes sense — the playful ways in which Quavo, Offset and Takeoff’s individual flows accentuate and compliment each other are always at their sharpest. Sleek production from Metro Boomin, Zaytoven, G Koop, Murda Beatz and more keep the record rolling replay after replay. “Slippery,” one of the more melodic cuts on the record, could’ve been Migos reaching toward pop-stylings; but, as it turned out, pop turned around and embraced them instead. — Steffanee Wang

[embedded content]

YouTube

Jonwayne, Rap Album Number Two

Log onto any website that centralizes left-of-center music and you’ll find dozens of releases authored by the Los Angeles rapper and producer Jonwayne. There are short, five-track EPs, compact discs dedicated to sampler machine workouts and collector-minded cassettes, all dating back to his emergence during the late aughts. But Rap Album Number Two feels like his first album that even casual listeners, unaware of his reputation among beat aficionados, should hear. He self-consciously marks a break between his newly sober state of mind and years of international tours, drunken antics and “being a burden to my people and alienating my fans,” as he puts it on “Afraid of Us.”

“I’ve been so caught up in the lack of acceptance / I never focused on the man to accept,” he raps on the same track. Yet, it’s the same talent for composing melodies and arrangements that initially drove his career that keeps this album buoyant. The ominous, striding piano that drives his most boastful track, “TED Talk,” and the airy strings that hover in his most haunting, remorseful number, “Paper,” make Rap Album Number Two more entertaining and insightful than a mere 12-step confession. — Mosi Reeves

[embedded content]

YouTube

Ill Camille, Heirloom

Back in July, on an episode of former NPR Music podcast Microphone Check, Ill Camille let co-hosts Frannie Kelley and Ali Shaheed Muhammad in on the key to her process of self-discovery. It comes in the form of a question she posed to herself at a critical juncture in her career: “‘What do I love about myself that I could magnify and talk about and celebrate?'”

The answer is infused throughout Heirloom, an album the L.A.-bred rapper took four years to craft and release. Like her smoky, seasoned vocals, Heirloom reflects the depth of her strength, pain and personal growth. In 2014, she lost three pillars of her family in her grandmother, father and an uncle. Despite being a fixture in L.A.’s hip-hop scene known for collaborating with various Top Dawg Entertainment artists, contributing to Kendrick Lamar’s Good Kid, M.A.A.D. City and featuring TDE President Terrence “Punch” Henderson on Heirloom‘s “Sao Paulo,” she took time out after her 2013 release Illustrated to live at the speed of life. The result is an album that echoes her deep-rooted appreciation for family, respect for community and love of self. With production from the likes of West Coast legend Battlecat and others, it’s a jazzy meditation on L.A. authenticity. — Rodney Carmichael

[embedded content]

YouTube

Brockhampton, Saturation III

By some accounts, a 12-member hip-hop boy band dropping three albums within a year’s time is textbook over-saturation. But that’s just what the members of Texas-based crew BROCKHAMPTON want you to believe. BROCKHAMPTON’s vibrant and declarative ethos is injecting hip-hop with something new.

Saturation III, the band’s third and strongest album in its 2017 series, finds Kevin Abstract, Ameer Vann, Matt Champion and company more focused than ever; no longer a bunch of kids taking turns rhyming on a beat but deliberate, exciting storytellers. “BOOGIE,” the album’s high-adrenaline opener pulls the listener in, “HOTTIE” serves up pop-inclined hooks while touching on haplessness, and “STAIN” brings haters in on the narrative. Production on the album is also handled by crew members, mainly Romil Hemnani and Jabari Manwa.

The band of misfit brothers move as one — rappers, producers, engineers and webmaster included — and are occupying a space in rap that, until recent history, didn’t really exist. With more music from BROCKHAMPTON due out in early 2018, the guys will undoubtedly continue to shatter boundaries and redefine the capabilities of a rap collective. — Sidney Madden

[embedded content]

YouTube

Courtesy of the artist

GoldLink, At What Cost

On his 2015 album And After That, We Didn’t Talk, GoldLink spoke this moment into existence. In “Palm Trees,” a song about a character who tries to convince a woman to let him back in, he talks about an escape: “Underneath the palm trees / You can leave your worries.” But he also talks about a responsibility: “You know that I need to bring my city back,” he raps melodically, with conviction.

GoldLink has always been talking about home, but on At What Cost, he really takes us there, into the idiosyncrasies of the DMV, particularly the areas of D.C. and Prince George’s County where he spent the most time growing up. He documents the specificity of his generation: kids whose parents had to contend with the crack era, kids who caught the very end of go-go music’s cultural dominance, kids who still remember an earlier, less gentrified iteration of the city and know intimately what has – and hasn’t – changed. The album is a narrative about infatuation and destructive rivalries, told through rich and layered references outsiders have to Google. It feels like GoldLink made it for people who needed hip-hop to finally acknowledge their particular reality. The result is journalistic, like a timeless documentary. — Jenny Gathright

[embedded content]

YouTube

Tyler, the Creator, Flower Boy

Either Tyler, the Creator is undergoing a drastic growth spurt or he’s smarter than we’ve given him credit for. The shock-and-awe approach of his early work garnered plenty of detractors, but also a rabid fan base. The common thread we all shared was our impulse to hear and see what was next. Then, “Treehome95” from 2013’s Wolf album happened and the gradual shift started, with more signs of Tyler the conductor veering through on Cherry Bomb. On Flower Boy (promoted as Scum F*** Flower Boy), he presents the previously hidden core of his former self. His Bastard skin is almost completely shed here, with only a few remnants of the old Tyler left behind on “Who Dat Boy” and “Ain’t Got Time.” We get quality over quantity in regard to bars, with the heaviest emphasis on pristine production. The manic drums and distorted synths are swapped out for delicate string arrangements and chord progressions. In the future, I can totally see Tyler delving further down the path of his idol, Pharrell, by scoring movies and getting his Quincy Jones on for more musicians. So are we witnessing the unveiling of Tyler Okonma or another strategic plot of a longer storyline? I would say a lot of both. — Bobby Carter

[embedded content]

YouTube

CyHi The Prynce, No Dope On Sundays

It’s easy to forget the secret weapon behind Kanye West’s lyrical conceit for his last few albums happens to hail from Atlanta. The city has garnered so much flak in recent years for accelerating false dope-boy narratives and deemphasizing the King’s English for sing-songy melody in ways that perpetuate stereotypes about inarticulate black men. But this is the same town that begot Andre 3K’s poetry, Ludacris’ punchlines, and Killer Mike’s political heat. Then there’s CyHi The Prynce of G.O.O.D. Music fame. The only reason his name hasn’t rung out among the city’s greats until now, despite releasing several hard mixtapes, is because he didn’t have a studio album. That finally changed with the long-awaited release of No Dope On Sundays. And here’s the genius of his project: he takes the city’s drug-trappin’ trope and flips on its head. Because, once upon a time in Atlanta, real dope boys recognized the Sabbath, too. If not to express their faith in God, then out of fear of the Red Dog police unit — which was known for making sweeps at the most disrespectful times. CyHi’s lyrical display here, full of sharp metaphors and ill wordplay, is praiseworthy in itself. But it’s the redemption he squeezes in, even as he fleshes out his own duality, that takes No Dope On Sundays to a higher plateau. — Rodney Carmichael

[embedded content]

YouTube

Jay-Z, 4:44

As an avatar of black capitalism, Jay-Z has long toggled between touting his own specialness and generously spreading the gospel to us unlucky, decidedly poorer souls. 4:44 falls into the latter category, as he casts his oft-criticized TIDAL venture as a black power stake in the digital musical economy, and offers suggestions on “Family Feud” like: “What’s better than one billionaire?” (“Two,” his wife Beyoncé Knowles coos appreciatively.)

In spite of natural opposition to American youth’s current bout with socialism – or rather, his zeal to appropriate that moment as thoroughly as a late ’70s post-Black Panther mayoral candidate – Jay-Z remains a charming and persuasive performer. He gives us tales that deepen the myth surrounding him, from confessions of marital unfaithfulness on the title track to autobiographical revelations on “Marcy Me” and “Smile.” He collaborated with producer No I.D. on its music, full of samples of Stevie Wonder and Donny Hathaway. It feels unfussy and earthy, akin to listening to a favorite uncle expound in his leather chair as a warm fire crackles and a record player hums away. And though Jay-Z’s suggestion that we all can be financially wealthy if we work hard enough seems patronizing and ridiculous, we’re happy to hear a few tall tales from him, anyway. — Mosi Reeves

[embedded content]

YouTube

Future, HNDRXX

Men are socialized to suppress emotion. That goes doubly for brothers operating in a genre where toxic masculinity and misogyny are not only celebrated, but rewarded with royalties. No wonder, then, that it took Future so long to escape the trappings of his success. I’ve already written about why this LP is one of the best R&B albums of the year, so it might seem like a contradiction to argue for its inclusion here. But if any album highlights an artist pushing back at aesthetic limitations, it’s Future’s HNDRXX. This is the project Atlanta’s resident astronaut has been dying to release since his stratospheric rise. Remember his sophomore outing, Honest? Future had to backpedal after its release to regain the streets, and he went on an extended mixtape tear of rachet trap anthems to do so. That output was much grittier and gutter than the pop-friendly melodies that peppered the 2014 LP. It’s as if fans weren’t ready to embrace him in all his naked Honest-y. His return three years later to a similar state of vulnerability — this time exacerbated by his public breakup with former fiancée Ciara — gave him even more emotion fuel to exhaust. It’s a stunningly glorious display of male ego and excess, the kind that could only come from a man scorned. But between its bitter lines, Future reveals a heart victimized by the same emotional cesspool he’s drowning in, even as he gurgles his last Auto-Tuned breath. — Rodney Carmichael

[embedded content]

YouTube

Rapsody, Laila’s Wisdom

Praising Laila’s Wisdom for the way it centered black women feels like the lazy route, when really, it stands out for its commentary on many other things: relationships and power, the music industry, a political moment where it feels like everyone has a platform but no one knows anything at all. Luscious hooks from the likes of Anderson .Paak, BJ the Chicago Kid and the Canadian singer Merna (whose contribution to “You Should Know” is truly something worth dwelling on) give the album its rich texture. So do other big-name features: Kendrick Lamar, Busta Rhymes. But the best parts of the album are the long stretches where Rapsody is just rapping, generating polyrhythms better than almost anyone doing it today, wielding the kind of wordplay we’re often told the people don’t appreciate enough anymore.

I won’t congratulate Laila’s Wisdom for merely existing. I’ll honor it for being the album I ended up returning to, over and over, for a reminder of what it looks like to defy anyone who tells you to only exist within the critical frame they made for you. The lyric I’m stuck on is in “Black and Ugly.” It’s a reference to Biggie’s “One More Chance” remix: “Black and ugly and still nobody fine as me.” — Jenny Gathright

[embedded content]

YouTube

Lil Uzi Vert, Luv Is Rage 2

“Higher than Elon Musk,” brags Lil Uzi Vert on “Neon Guts” as Pharrell Williams backs him with his inimical blend of dirty keyboards and heartfelt melody. The standout track isn’t the only sign that Lil Uzi Vert’s most popular album to date is the latest evolution in sing-songy pop-rap. On “Malfunction,” he sounds just like Wiz Khalifa; on “Early 20 Rager,” he carries the “rager baton” that was once kicked off by Kid Cudi. The Philadelphia hip-hop vocalist deserves some credit for fueling a widespread trend among rappers of patterning syllables against the beats. “I’m the one who really started all this,” he sings on “Two.” He adds a few emo touches to his performance, chiefly on the massive hit, “XO TOUR Llif3,” where a girlfriend tells him, nihilistically: “All my friends are dead / Push me to the edge.” But for every short plunge into narcotic darkness, like on “Feelings Mutual,” there’s a bigger splash of comforting harmonic braggadocio. Lil Uzi Vert may be aware of his mortality, but he’s too busy having fun to get lost in depression. — Mosi Reeves

[embedded content]

YouTube

Kendrick Lamar, DAMN.

The loquacious Kendrick Lamar is manna for decoder ring researchers, whom believe that any act of creativity can be unpacked into discrete, explainable parts. Still, all of the theses, thinkpieces and deep-dive analyses surrounding Lamar’s latest masterwork – his Christian faith, his blackness, his theories about karma and his fascination with his own physical demise – can’t quite describe the air of haunting sadness that hovers over it all. Is it simply by-product of an era in which pop music has grown thematically despondent, prone to expressions of chemical abuse and suicidal thoughts? Is it the big comedown after a traumatic 2016 electoral season? Is it fatalism over our ability to evolve into loving, empathetic beings, resulting in the disembodied voice of Bekon singing on “Pride,” “Lust’s gonna get you killed / But pride’s gonna be the death of you, and you, and me …”?

DAMN. may be the most despairing of Lamar’s albums, a feeling that his affirmations of faith on “Loyalty” and “Duckworth” can’t quite absolve. It’s soaked in the notion that faith of any kind means sacrifice, with only the belief that your good works will be appreciated long after you’ve ascended to the afterlife to sustain you. — Mosi Reeves

[embedded content]

YouTube

Courtesy of the artist

Open Mike Eagle, Brick Body Kids Still Daydream

The projects have played backdrop to many of rap’s greatest fairy tales. Jay-Z slung his way through Marcy Houses, Prodigy survived LeFrak City, Ol’ Dirty Bastard characterized the Whitman Houses as a zoo and Nas used Queensbridge Houses as cover art to illustrate his struggle. But while images of the projects, and those who live in them, often get boiled down to one dimension, the distinct ethnic enclave born from these worlds is rarely highlighted.

Chicago-born MC Open Mike Eagle does just that as he brings The Robert Taylor Homes to life for his 2017 album Brick Body Kids Still Daydream. The Robert Taylor Homes were demolished in 2007, but once stood as the nation’s largest public housing project. Mike grew up in those projects by way of relatives who lived there. For the rapper, the Homes held experiences and stories that helped shape his identity. From the pragmatic and powerful “Brick Body Complex” to the listless “(How Could Anybody) Feel at Home” and the sorrowful “My Auntie’s Building,” Mike spits from an array of different perspectives, almost as if he’s living in a memory of the place he grew up.

Brick Body Kids Still Daydream occupies a special space in the landscape of hip-hop this year because it approaches the politics of erasure and black displacement in a personal way, while still showcasing the simple joys of project-raised kids. We all could use more ghetto superheroes. — Sidney Madden

[embedded content]

YouTube